Arrowheads

For many of us, finding an arrowhead in the field becomes an interesting link to the past, a pause in the busy swirl of daily life, to reflect on days gone by. Some finds are just happenstance, but like birdwatching, by selecting certain times and places, and focusing on that theme, you can increase the odds in your favor.

His arrowhead display.

Our close family friend grew up in and around the town of Oxford on the west side of Johnson County, and as a boy he would walk or ride his bike to sandy cornfields recently plowed or disced, preferably after a rain, and just slowly walk a pattern, focusing on a small area ahead of him. He gradually made a collection of only the most perfect arrowheads, mounted them in a pair of homemade picture frames, and they are still on his wall. One of his grandmothers was a local tribal person, so the arrowheads he found may have been used by his ancestors.

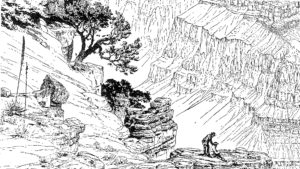

A portion of an early illustration of the Grand Canyon. https://archive.org/details/tertiaryhistoryo00dutt/page/n229

My own best experience with arrowheads was in the mid-1960s on the south rim of the Grand Canyon.

After exploring the canyon edge for a half day and trying to identify the far side formations, matching them to their field guide descriptions, I started following faint game trails back into the bushes, going away from the rim, to learn who made them and where they went. Back there, I found a slab of rock propped up like a couch cushion and in front of it was a collection of debitage, the chips left by an arrowsmith. It was a triangular layer, thick on two edges and thinning gradually on the third. When I sat down with my back against the slab and my legs apart against the two thick edges, it was clear that someone else had sat here a long time ago just like this, flaking flint, with the chips accumulating between his legs.

I ran through the chips with my fingers and there seemed to be a couple of broken tips but no bases, so I figured that the maker had salvaged the bases by reshaping them into a wider tip. Several larger chunks with conchoidal fractures running down the sides were nearby, which I assumed were the cores he was spalling the arrowhead flakes off of. I toyed with the notion of taking the cores with me to see if I could obtain the fingerprints of the guy, but this lonesome piece of information wouldn’t be worth much out of context.

I wanted to return to the site someday in the future, so I carefully noted its location. When I did return nearly two decades later, it was under a parking lot.

I don’t collect arrowheads. But when I find one, I like to examine it in detail for wear, breakage, reworking, stains, rock type, context, etc. And then I put it back for someone else to find and consider the past.

A handful of modern obsidian arrowheads from Alaska.

When I worked in Alaska around the turn of the century, I met a guy who made obsidian arrowheads to sell to tourists. Once he had shaped a core from an obsidian cobble, he could pop off a large flake and pressure flake it into a sharp-edged arrowhead in a few minutes, which was so little effort that they sold for a dollar.

The literature indicates that Midwestern Native American arrowsmiths were similarly efficient working with flint, chert, novaculite, and other flakeable rocks with conchoidal fracture. In some tribes this was the assignment of men too injured to too elderly to hunt or go to war.

So to my way of thinking, finding arrowheads is similar to birdwatching – requiring similar attention to the landscape, an opportunity to ponder what they are, and how they got there. And I don’t have any reason to collect a lot of birds or arrowheads. One place to improve your odds of finding arrowheads is to go to a Bur Oak Land Trust property a week or so after a controlled burn, which has been followed by a rain that dissolves some of the ash and exposes the soil.