Attract Hummingbirds with Native Honeysuckle

Hummingbirds live their lives at a frantic pace, as shown by the fact that if you hold one in your hand its heartbeat is so fast that you cannot even sense it. Their metabolism can only be described as furious, in part due to their diet of nectar. You’ve seen children go hyper on too much sugar, and for hummingbirds it’s all day, every day. In fact, going an entire summer day without nectar is a crisis and may mean the inability to even survive the night. Only in early autumn does the rubythroat bulk up on fat in preparation for migration. Therefore, hummers attempt to stake out summer territories, which will include a continuous sequence of blooms. Switching territories later is fraught with problems because so often the later flowers are already in some other hummer’s territory and the battle for access can become lose-lose for both hummers.

This is where land managers and gardeners can aid hummer survival, either by:

- A) Growing a mix of species that flower sequentially over the whole summer. (Our native prairies offer the template here. Mark Müller’s “Jewels of the Prairie – Blooming Dates” poster offers inspiration for selecting a season-long sequence.)

- B) Growing those few native species that can produce nectar all summer with just a bit of encouragement.

An interesting choice here, if you are going with plan B, is one of our native honeysuckles (Lonicera sempervirens), usually labeled in the nursery trade as trumpet honeysuckle, coral honeysuckle, or scarlet trumpet honeysuckle. This native honeysuckle is a somewhat variable species with flower color ranging from red to orange to yellow on different plants. But the shape of the flower is consistently a very slender long tube, which exactly matches a rubythroat’s bill and excludes most insects, suggesting the flower and hummer may have coevolved with each other. The variation also includes those which are covered with flowers for just a few weeks, and those which bloom more sparingly but all summer long. The selection labeled “Major Wheeler” by the nursery trade has an especially long blooming season in my yard, beginning just before the hummers arrive from the south, and continuing until well after they depart in the autumn.

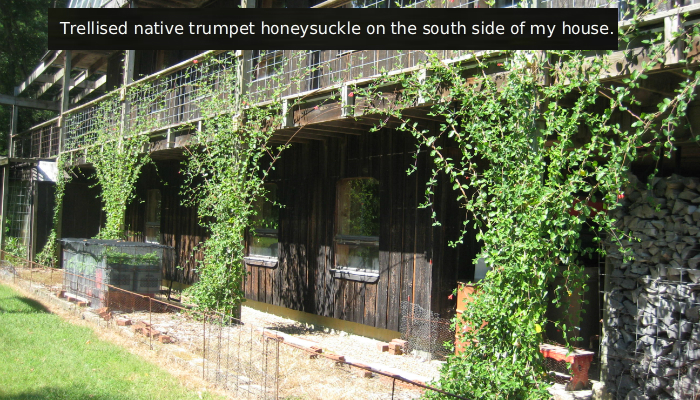

This relatively slender, graceful vine lends itself to growing on a sunny trellis. Last spring I built a set of fan-shaped trellises from thin steel rods on the south side of my house, where “Major Wheeler” specimens were started the previous year. It only took a bit of training and they figured out how to track up the fan shapes (see photo).

When the plants first bloomed, a female rubythroat staked out the whole array and vigorously defended it from other hummers. Then I noticed that she was regularly shuttling back and forth to a certain nearby tree branch tip that leaned toward the honeysuckle vines, and realized that she had built a nest there. About three weeks later, she flew from the nest area accompanied by a slightly smaller hummer that she was not aggressive toward, and it must have been mom and her kid, feeding from adjacent clusters of honeysuckle flowers. I had never seen this teaching moment before with hummers and probably only noticed it this time because it was on the balcony right outside our living room window.

Incidentally, trumpet honeysuckle is a well-behaved native to the US, not to be confused with the Amur honeysuckle or the Tatarian honeysuckle, which are two incredibly invasive Asian honeysuckles under attack by all conservationists. I’ve got more natural experiments started with the native honeysuckle species and will report back next winter.