Bladdernut: An Unfamiliar Native Shrub

The native shrub called bladdernut apparently used to be quite common around here based on reference to it in early literature. But a couple of decades ago, when I went looking for it in what should have been its favorite haunts, I couldn’t find any. Finally, I asked Jeff Schabilion, professor of botany, who grew up in southeast Iowa and always seemed to know about plants that most of us never heard of. He said the nearest patch he knew about was in the wooded ravine west of the newly built Carver-Hawkeye Arena. So they were, right here in town.

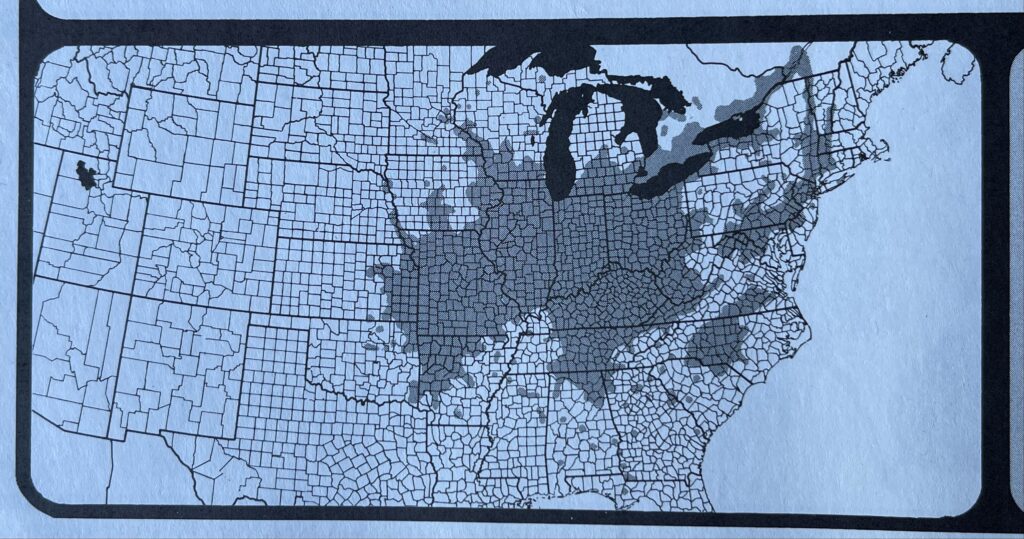

That autumn I gathered some of the papery seedpods, and after a long wait of several years, had some young plants at home. Like many of our native forest species, we are near the northwestern limits of its distribution, being limited to the north by winter temperatures, and to the west by scanty rainfall, dry air and fire. Browsing by deer, elk and bison probably also played some role, but even after last winter I still don’t understand this component.

Native distribution of bladdernut as illustrated in Gary Hightshoe’s comprehensive book, “Native Trees Shrubs and Vines for Urban and Rural America.”

Bladdernut is easily overlooked because in some seasons it resembles a shrubby little boxelder tree. The young branches of bladdernut have the same long, slender and smooth shape as young boxelder. In early summer, the leaves of both species are easily confused. But in spring, about the time bluebells and mayapples are blooming in the woods, bladdernut shrubs produce clusters of small white flowers that hang down like little bells. If you visit these flowers at night with a flashlight covered with a thin white cloth to just produce a soft glow, you might meet its pollinator, which is a tiny white nondescript moth that I have not successfully identified.

Left to right: Bladdernut leaves on one hand, young boxelder leaves on the other. Bladdernut flowers seen from below. By around Memorial Day the young seed capsules are a pale translucent green, and for a few weeks are conspicuous among the darker leaves. Photos by Kate Sulentic.

By late summer, the pollinated flowers have developed into three-sided papery capsules (bladders), which are rather large, but the same shade of green as the leaves. The bladders flutter in the breeze with the leaves, and are easily overlooked. In autumn, the hanging paper capsules turn brown like autumn leaves and each contains a nut or two the size of a pea. Sometime in winter the frail capsule detaches and is blown across the snow by the wind, which I suppose is a method of dispersal.

Once a young bladdernut plant becomes established and gets to be around four years old, it is still a slender little shrub, but it begins to send out a few root suckers and is on its way to forming a little open thicket. The root system is shallow and fibrous, so small suckers transplant easily away from the parent as a root ball, when still dormant of course. And being shallow, they dry out readily, so bladdernut thrives best in cool shady ravines, valley bottoms or low on north-facing slopes.

Its attraction to large browsers like deer is still a puzzle to me. I have two patches of bladdernut in our community, about a quarter-mile apart, one propagated clonally from the other, so they are genetically almost identical. Yet this past winter, one patch was extensively eaten by deer, and the other only lightly damaged. Direct observation and hoof prints in the snow show abundant deer in both locations. Another mystery of nature.