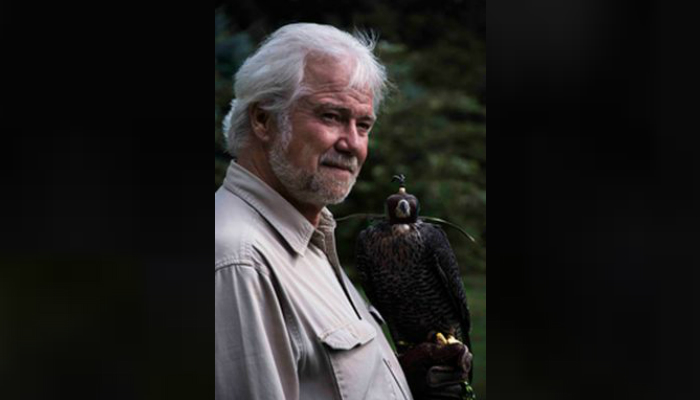

Bob Anderson, The Falcon Man

If you dig back behind environmental success stories, there is often one person whose efforts were the main driving force, and often these efforts cost them a lot.

Everyone knows that birds took a big hit from organochlorines, especially dieldrin and DDT, and especially the species near the top of their food chain due to biomagnification. Here in the upper Midwest, our subspecies of peregrine falcon became extinct in the wild and only a few semidomesticated ones were being flown by falconers. Bob Anderson was one of these falconers and he decided to devote his life to restoring a wild population.

Bob understood that this was not going to be an occasional effort. So he quit a good-paying job in Minneapolis and cashed in his retirement to launch his new career. Working with other falconers across the country, they developed a breeding program that produced chicks that could be “hacked” and imprinted on a suitable site. Hacking refers to feeding them chunks of meat like their parents would have, and doing it surreptitiously so they would never know a human was doing it and thereby becoming imprinted on us.

Bob began his hacking program high on tall downtown buildings, which had the advantage of easy access and freedom from some predators, like raccoons, plus possibilities for public viewing from nearby windows.

Education was also an important part of his meager income. I recall an evening program in Amana where Bob did a slide show about falcons, including breeding to retain the Midwestern subspecies. He also had his own peregrine tethered to a perch, and it was the first time many of us got to see a live one up close. When his sponsors “passed the hat” I noticed that there already were a lot of $50 and $100 bills in it, a vote of confidence as well as recognition that he was living on the edge. Specifically, he was living in a friend’s nearly abandoned farmhouse, and a visiting news reporter opened his fridge and found a lot of frozen domestic quail for his chicks and a half jar of peanut butter and some bread for Bob.

And the city hacking program was a success, which he and his volunteers gradually spread to other cities. By around 1990 a few of his chicks had returned to breed on high rooftops, upper bridge structures, and tall smokestacks bearing little nesting platforms, because that is where they were imprinted.

But this is not where Bob wanted them, his real goal was to return breeders to their historic cliffs along the upper Mississippi, and he met a lot of resistance to this plan. Biologists claimed that without parents to defend them, that predators would eat the hacked chicks. Also, new chicks were now worth more than their weight in gold, and his suppliers did not want to risk the possibility of failure of a cliff program. I attended the showdown meeting at McGregor, where Bob was greatly outnumbered by opponents. But he prevailed because everyone also recognized that the successful city program was his baby, and nobody else had the experience and dedication to move forward.

Half his life became one of scrambling up and down cliffs, scouting historic aeries and developing hacking plans for the most favorable, which included questions about proximity of great horned owls, kids with rifles, rock climbers, etc. The other half of his life became the search for volunteers and money. While in the field, he often slept in his car and lived on peanut butter sandwiches, pouring every penny possible into the cliff program.

His vindication came one day in 2000 when a young cliff-raised female recruited a city male and they successfully raised a family on her ledge. By 2011 Bob’s volunteers tallied 21 active nesting cliffs along the upper Mississippi, having recovered from zero. They were back!!!

As the peregrines needed less and less of his help, Bob expanded his scope to build the now well-known eagle nest cam at Decorah, plus osprey, owl, and kestrel cams.

Bob passed away in 2015, a life intensely lived, intensely focused and intensely satisfying.

As members of Bur Oak Land Trust, we have a built-in opportunity to get involved in conservation as much as we wish, as much as we can cope with, as much as we can afford. Our personal program could be uncommon critters like ornate box turtles or rare butterflies or uncommon plant communities like dry prairie or oak savanna. Or maintenance to upgrade an existing parcel to all natives; or trails and access; or programs for children; or nesting habitat for uncommon birds; or …. If you need a place to get started, call Jason Taylor, our new and very well-qualified land manager, at 319-337-7030.

photo taken from Kirkwood Community College News: Global Internet Sensation to Land at Kirkwood