Burials On The Prairie: Dickson Mounds

Many years ago, I think it was 1972, I visited a unique place in central Illinois called Dickson Mounds. The story promoted at that time was that plowing during the Depression Era on the Dickson farm would turn up human bones. The owner, Don Dickson, didn’t wish to just leave them there to be scattered around, so he would dig up the rest of the shallow grave and salvage the rest of the skeleton plus whatever grave goods accompanied it. Still not knowing what to do with it, he would pack it all in boxes stashed in his barn. In subsequent years, the process was repeated until he had more than 200 boxes in his barn.

I’ve heard other versions of the above story, but all agree that by the WWII era he had built a building over part of this Native American cemetery, dug many new, closely spaced open graves and reassembled individual skeletons in them. He ran it as a tourist attraction where for a fee you could wander between the open graves. Problems developed with theft and collapse of the sidewalls of the graves.

By the time I visited, the state of Illinois had built a more permanent building, the access was more limited, mostly to a raised balcony around the perimeter which allowed you to look directly down into the open graves at quite close range. With close-up binoculars or a telephoto lens, you could see intimate details like chipped teeth or the flaking pattern on a flint arrowhead. The most popular grave was the skeleton of a young woman holding the skeleton of a baby in nursing position. I do not know whether they were originally found this way or assembled later for added drama.

There is a long history of Native Americans not wanting their image captured. For example, consider the maneuvering that painter George Catlin had to do here in the Midwest in the early 1830s in order to get permission to portrait the native people. So when I entered the building and saw open graves and flashbulbs popping I immediately thought that photography was a bad idea and retreated to take my camera back to the car. Actually the whole display seemed beyond tacky and it had obviously been built over the objections of modern native people.

The archeologists had of course gotten involved and determined that the Dickson display was only a small part of a much larger cemetery complex. There

was actually a cluster of low mounds and flatland cemeteries built in various

ways, which collectively held more than 3,000 separate burials. These spanned from about 1,200 to around 800 years ago. They also found the remnants of a village in and around the burial grounds, all of which is located atop a bluff overlooking the Illinois River.

The archeological story that evolved was that the area originally harbored a small hunter-gatherer society who lived in the general area in permanent or semi-permanent camps. The condition of their bones, both physical

and chemical, plus grave goods, indicate a robust healthy people. They were living off the prairie-savanna uplands, plus the large wetland and river complex below the bluff (today called the Emiq uon wetlands).

But as several centuries ticked by, the population greatly increased and corn became an increasingly important part of their diet (perhaps necessitated by overhunting and over-collecting of the native animals and plants). One consequence of eating a lot of corn is that it shortchanges people of the vitamin niacin, which was documented in the burials as shorter life spans, rickets, more

deformities and general malnourishment.

At the time of my visit, the state of Illinois was still in the process of taking over ownership and management of the site. Several decades later, the voices of the modern native people were finally acknowledged as relevant and in 1992, the governor of Illinois ordered the open graves to be covered. With its main attraction now out of sight, the building was repurposed to display themes like the original ecosystems of the area, the native peoples lifestyles, settlement patterns, trade patterns, and the changes brought by increasing use of corn in their diets.

So it has been a half-century since I’ve been there, and in the meantime we have learned a lot more about prairies, savannas, wetlands and the native people who helped shape them as ecosystems. If you visit, you will hopefully find it kept

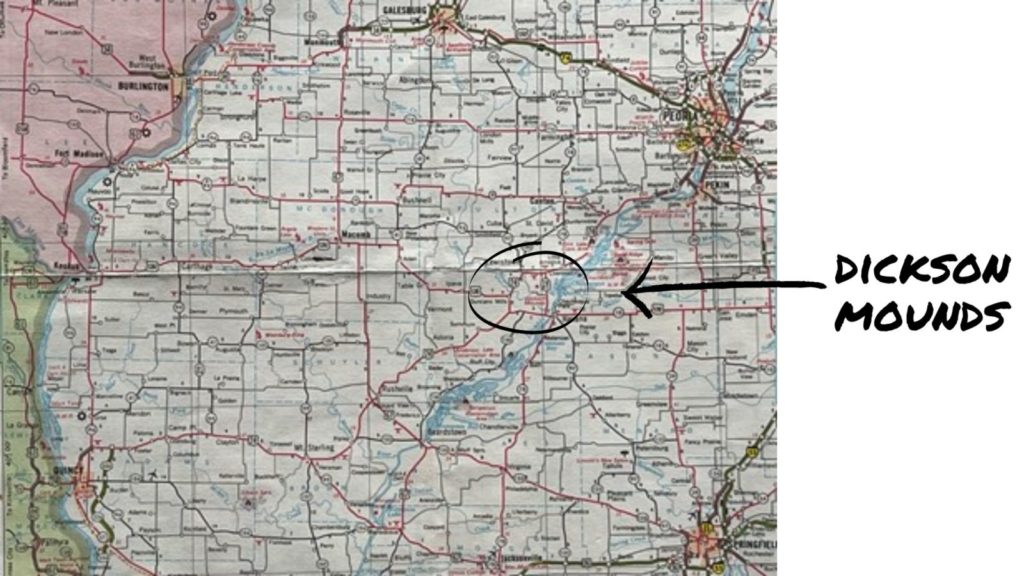

up to date. The site is located 66 miles due east of Keokuk, Iowa, “as the crow flies.” But assuming you stay on the roads, the map might help you get there.

For more about the site, visit the Illinois State Museum online.

Tags: burial mounds, dickson mounds, illinois, Indigenous People, Lon Drake, native american, Native People, prairie, preservation