The Burning Butterfly Problem

I went out to hunt up a couple of pawpaws late in the afternoon in late September, and noticed a couple of monarchs drifting by. The media has already turned its attention to this amazing annual migration, the milkweed shortage, the failing winter habitat in Mexico, and the general decline of most butterfly species. Many of these stories also promote planting butterfly gardens; and this is where their advice often falls short, and can become a disservice to the butterflies. Let’s complete the story to make this really work.

Most butterfly species are not fussy about which plants supply their nectar, and many of them lay their eggs on or near the food plants for their next generation of caterpillars. When the caterpillars are winding down their portion of their life cycle, they in turn build chrysalids on or near their host plants to winter over. In nature, this is a good plan. But in our gardens, most folks “clean up” in autumn or early spring, raking, burning, and/or throwing away the dead or dormant stems and leaf litter into the trash. They don’t realize that they have also “cleaned up” the next generation of butterflies, which were dormant somewhere in those dead stems, leaf litter, or the shallow soil now tilled.

So the message today is to please design and manage your butterfly garden to be left untidy over winter and far enough into spring until your chrysalids have had time to metamorphose, emerge, and fly off – which varies amongst different species. If you need flowers all season, consider maintaining two butterfly gardens so the younger one can have seedlings coming up, and the older “trashy” one can be carrying over last year’s butterfly genes.

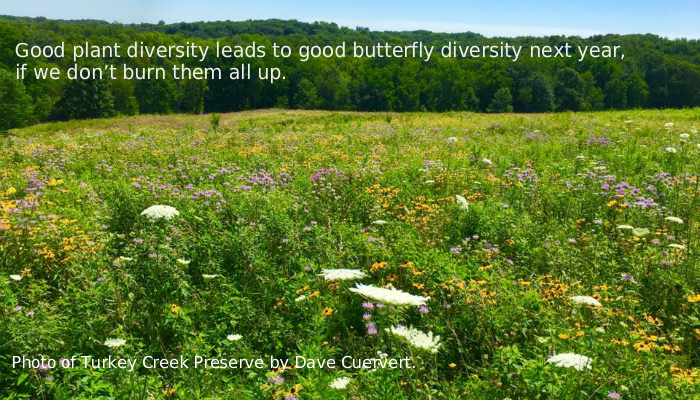

The same concern applies to burning prairies, both remnant and planted. Dennis Schlicht, lead author of Butterflies of Iowa, has preached for decades that too regular and too complete burning is detrimental to butterflies. His evidence includes the fact that some remnants have lost their populations of rare/uncommon/endangered natives only after regular burning began as a management tool.

Solutions to avoid burning all the butterflies in prairies include:

- Patchy burns: I prefer to light my spring burns in the early evening, because the wind often dies down and the dew begins to settle. Under these conditions, the fire advances more slowly and cooler, leaving irregular patches unburned, which continue to support butterflies and other native insects. The following year, these unburned patches contain more dead vegetation and are more likely to burn, but will leave other patches unburned.

- Rotational burns: You can divide your prairie parcel, with permanent or temporary firebreaks, into several sectors and burn on a 3- or 4-year rotation. To create the most diversity, arrange the firebreak lanes to split each available microhabitat on the property (wetter, dryer, weedier, more stony, …)

So, to summarize, when planning a butterfly garden – or habitat used by butterflies – we really need to accommodate their entire life cycles. Failure to do so can result in luring them to a site that may provide entertainment for us but be a dead end for their continued success.