Cabinets of Curiosities Become Collections

The cabinets of curiosities of the 1600s and 1700s, scattered across Europe, raised some good questions about the life and the geology of our planet. But they were too limited to provide good answers. By the 1800s certain oceanic trade routes were well-established, and Britain especially regularly sent out mapping expeditions the primary assignment to get a better fix on the locations of continents and islands, and along the way, learn what they could about ocean currents, climate, weather, plants, animals and native people. This regular collecting lead to the creation of specialized public and private collections and museums.

The mapping ship, the Beagle, was sent out again at the end of 1831, and during a last-minute shuffle of personnel, a young and inexperienced fellow named Charles Darwin was given the position of naturalist for the 5-year tour. This experience set him to thinking that within the great variation within a species only a favored few would survive to pass their traits on to the next generation. Over many generations they could slowly evolve into a separate species and may well outcompete their parent species. He even hypothesized that the mechanism of transfer of variation was tiny specks of living matter, too small to be seen, but acting as templates for growth. He called these gemmules, today we call them genes.

Darwin also realized that he had only seen a tiny bit of the world on his travels on the Beagle, so he established a broad correspondence. His historians so far today have originals or copies of more than 14,000 letters he either wrote or received in his worldwide search into the variation and origins of species. He chose barnacles to study in detail, in part because at almost any marine boat landing in the world, a correspondent could scrape a handful of them off a rock or pier at low tide, put them in a bottle of alcohol, and ship them to him. He also raised domestic pigeons because there was so much variation amongst them, even though all had been originally bred from the wild rock pigeon.

As Darwin’s database and studies grew more convincing, it also became more clear that us humans were not some special creation but merely one direction that evolution of the primate line had taken. He could foresee the firestorm of controversy and hostility which would descend on him when he published his observations and conclusions. Only a century before he would have been burned at the stake. So while he shared his research with colleagues, his growing manuscript was repeatedly set aside. His preference was to stall long enough that it would be published after he died and he would be beyond threats and persecution. That is not what happened.

A young field collector named Alfred Wallace was working in the Indonesian islands in 1858. He knew Darwin, and observed, thought about, and marveled at the great variation within and between species. He had the advantage of more or less being on his own schedule and when he chose he could devote days to just observing to learn what different variations meant in terms of predation, breeding success and other survival factors, and pass this on to his patrons for their cabinet and museum displays. One week when he was too sick to do field work, he wrote a 20-page letter-manuscript to Darwin detailing survival of the fittest, and how that lead to creation of new species as habitat and environment changed.

Darwin was aghast. He had thought that he didn’t care whether someone beat him to taking credit for “his” natural selection and origin of species hypothesis. But now that Wallace had independently developed the concept from much more limited evidence, Darwin had to admit that he really did care and wanted credit, or at least partial credit for the discovery. Darwin’s sense of fairness and honesty prevailed, and he arranged through fellow scientist friends Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker to have both Wallace’s entire 20-page letter and an excerpt from his own 1844 manuscript read on July 1, 1958, at a meeting of the Linnean Society. Interestingly, neither author was present. Darwin’s son had just died and he was at the funeral. Wallace was in New Guinea hunting bird-of-paradise specimens for collectors and museums.

Darwin finally published his “On the Origins of Species by Means of Natural Selection,” on Nov. 24, 1859, and credited Wallace and several others. Due to his decades of research and correspondence combined with his field research on the Beagle and his high social standing in an exceedingly class-conscious Europe, his book was immediately read and well-received by the scientific community. Wallace never published his letter-manuscript and was delighted to have been part of the discovery process. In a letter to Darwin in 1864, he acknowledged that as a mere field collector he didn’t have the research experience to convince the scientists, nor the social status to tempt a publisher, “whereas your book has revolutionized the study of Natural History and carried away captive the best men of the present age.”

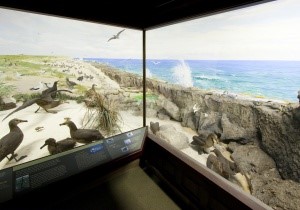

Overall, the Darwin-Wallace natural selection hypothesis quickly gained traction in the world of science because so many formerly independent lines of evidence all converged here. Some museums responded to the public interest in evolution and shifted to extensive use of dioramas to feature the habitat theme including some of the environmental factors which lead to the variation within and between species.

Today these same themes can be tweaked to emphasize endangered species, conservation and restoration. Has your favorite museum adapted to include modern conservation themes? As our storyline shifts from cabinets of curiosities to specialized collections to museums, one name stands out, for better and for worse. Stay tuned next week.