Climate II: Climate Change

In 1974, Dick Baker and I were teaching an introductory environmental class at the University of Iowa. One of our guest speakers was from a government agency in Colorado – probably the predecessor to NOAA – and he focused on the coming changes in global climate. He observed the underlying cause was runaway population growth, and showed evidence that the immediate driver of change would be increases in atmospheric CO2.

When he pursued the mechanism, his explanation was that our atmosphere is a heat engine, and if we run it hotter, the extremes are going to tend to become more extreme, both in terms of what does happen, and does not happen at any one place. For example, droughts tend to grow over months around some hub, with a regular failure to rain in one area, perhaps eastern Oklahoma, and then around it are many areas of skimpy rain, but not complete failure. If the heat engine cranks up more aggressively, the drought hub might grow, or might diminish, or might shift its location.

Our local drought pattern, here in southeast Iowa, has been one of decreased intensity over the past century. While the “dirty thirties” were a problem here, eastern Iowa still gained a reputation as the place “where it always rained – just in time,” meaning that farmers who still had good soils tended to have smaller yields, but not total failure of crops. Our drought of the 1950s was less severe than the 1930s. The drought of 1978-79 was still less severe, and the 2005 drought only continued into early 2006 before ending.

Our local rainfall seems to be developing some greater intensities. In 1993, a hub of increased precipitation was centered on central Iowa, and here locally our yearly total was about double the long-term annual average. On the uplands this was still manageable because it just rained about twice each week, and there was time between storms for runoff to drain away. But “away” was the larger drainageways. For example, the Coralville Reservoir that summer had an inflow thirteen times the storage capacity of the faculty, and the dam became a rather minor barrier to the river’s flow. The floods of 2008 here were somewhat larger than those of 1993.

Our ordinary rainfall here is becoming a bit more regular and abundant, and in general we are gradually favoring forest over prairie. The climatic models suggest a gradual shift to more precipitation and less drought around here, and that seems to be our evolving pattern.

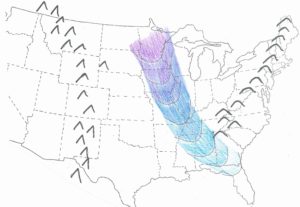

Temperature profile of the core of a polar vortex for a day or so before it is shredded going through the Appalachians. Pale blue is nearly freezing, dark purple is around -30°F.

An individual air mass cannot move much unless some other adjacent air mass begins to relinquish its position or its volume. We notice this, for example, in the winter when a great bubble of heated north Pacific air tries to push its way northward into the Arctic, and a mass of Arctic air has to go someplace. Sometimes it spills southward and tracks down the chute between the Rockies and the Appalachians. This is our polar vortex (the label vortex just acknowledges that all these air masses are also rotating). As the cold vortex slides southward, it is also being pushed eastward by the Prevailing Westerlies and becomes shaped into an elongating lobe by the resistance of the Appalachians. When the vortex moves briskly, Iowa’s lowest temperatures arrive about a day before nearly freezing weather spills into northern Florida. If it moves slowly, the Prevailing Westerlies smear out this cold core or break it up.

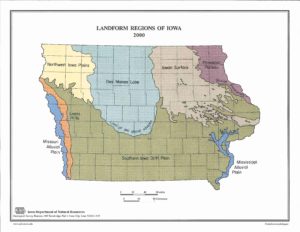

The Des Moines glacial lobe in northcentral Iowa.

Under slightly different preconditions, a vortex can instead break out into northern Europe or Asia pushed by the same driver from the overheated north Pacific. Yes, global warming can create some pretty cold weather for us on occasion. There is an interesting bit of evidence that this process has a long history. The location and shape of the Des Moines glacial lobe suggests that a more intense or more regular polar vortex helped winter snow to last longer 15000 years ago, keeping the glacial lobe alive longer.

In the Midwest, our climatic processes are already well established, mostly locked in by immutable geography. Climate change is for us mostly a shifting in the intensity, frequency, duration, timing, or regularity of these processes.

In some locations, like melting in the Arctic and rising sea level along the coasts, these effects of climate change are obvious because they can be measured and evaluated separately. But here in the Midwest, they merge with preexisting conditions and individual events like drought or a flood are harder to assign a probability that they are in part or entirely a consequence of the change. But the big picture – the world view – the modeling, all demonstrate that the change is real and is gradually getting out of hand for more and more ecosystems and the people who depend on them. The words “climatic refugee” were unknown only a couple decades ago, while today it’s becoming a reality. We need to start doing our share to slow this down.