Coralberry: Opportunity for Pollinators and Birds

Our native coralberry, AKA Indian current and buckbrush, is pretty much ignored by conservationists. It is a small shrub, often spindly when growing in shade, with pale greenish or pinkish flowers so tiny that we have to deliberately search to find them.

In the 1990s, my student Matt was interested in studying Walnut Creek, located east of Des Moines, because part of its watershed was going to be planted back to prairie, and we wanted to know how this would affect the creek’s hydrology (today this is the Neil Smith National Wildlife Refuge). On our first trip there, I happened to encounter a coralberry shrub, which was a dense little thicket of fine branches and had an abundance of fruit. So on a later mid-winter revisit, I took some cuttings to propagate it. A few years later I had a similar experience with a pretty specimen growing on “government land” beside the Coralville Reservoir. The species propagates readily from cuttings, and sprawls out by runners into a low, dense thicket, and today I have several low hedgerows plus a couple of room-size thickets at home.

Coralberry is best known for its annual crop of little pinky/purple birdberries. According to Degraaf & Witman (Trees, Shrubs & vines for Attracting Birds, 1974), birds that eat the berries include:

Ruffled Grouse

Bobwhite

Ringnecked Pheasant

Brown Thrusher

Hermit Thrush

American Robin

Cedar Waxwing

Warbling Vireo

Evening Grosbeak

Purple Finch

Pine Grosbeak

Not mentioned in their book is that here in Iowa, if you watch carefully, a flock of cedar waxwings sometimes also contains a couple of Bohemian waxwings, an elegant western bird that occasionally drifts eastward to join its cousins. Your odds of seeing them improve if winter fruiting plants are growing in your yard.

But to me, the most amazing aspect of coralberry is that its tiny flowers are such good nectar producers. In late summer – its main flowering time – the shrubs are abuzz with bumblebees, honeybees, mason bees, and little waspy insects with iridescent purple wings I cannot identify. My hummingbirds also hover their way steadily along the hedgerow, sampling the exposed teeny flowers – and probably teeny insects – without going down into the thicket. I’m certain that the main attraction for the bees is nectar because the honeybees’ pollen baskets remain quite empty no matter how long they forage.

But butterflies are not particularly attracted, and I think that it is because the plant offers no landing platforms, compared to sunflowers or monarda or milkweed; and butterflies usually do not hover to feed, nor do they climb down into thickets to chase down hidden flowers.

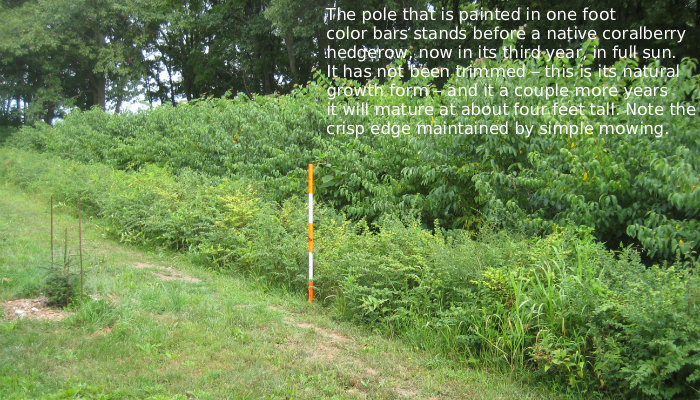

Coralberry is a tolerant plant, at its best with full sun and moist soil, lightly mulched. Its aboveground runners remind me of the growth form of strawberries, and while it really wants to sprawl out into a thicket, I have found it easily contained by regularly mowing a lawn or a trail beside it. I have not tested it yet with fire and do not know how readily it spreads into planted prairie.

The coralberry genus (Symphoricarpus) has about a dozen species in the continental USA – mostly the western part. During the last decade, nurseries have begun hybridizing them to produce bigger berries, variegated leaves, and other gimmicky traits, which can be glorified in their catalogues. I see no point in pursuing these when our native is already so hardy and so useful and so easy to grow.

Maybe you should try this native in your own landscape.