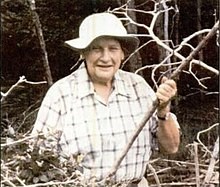

Cornelia Cameron: Our Peat Lady

Some time ago, late in the last century, an older lady named Cornelia Cameron took Sandy Rhodes and I on a little field trip to the westside outskirts of University Heights and Iowa City. She had been born and raised on a farm just south of what is now Finkbine Golf Course, when Melrose Avenue was still a dirt track.

Her dad was a professor of the natural sciences at the University, but he died when she was a small child. Her mom continued to mentor her in the sciences and was very well-qualified, having a master’s degree in geology and a doctorate in botany. As Cornelia matured, she attended the State University of Iowa (which today we just call the University of Iowa) for bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the sciences, and then earned a doctorate here in geology.

Cornelia forged a career as the peat specialist with the U.S. Geological Survey, and wherever U.S. interests got involved with peat and peatlands, she was sent there to collect data, answer questions and collaborate. We here in Iowa don’t think about peat very often, hardly having any. But in the more northerly climates of Alaska, Canada, western Europe and Russia, peatlands cover vast areas.

During WWII, one of the questions that arose about landing aircraft on peatlands was regarding loadbearing capacity. What does it take to build a functional runway? What is the frost heave in winter? And so on. Another question involved peat as a fuel in remote electric power plants and addressed topics including water content, depth of freezing, permafrost, calories available, ash, distribution of the resource, etc. She also worked on the more geologic aspects of peat as a precursor to coal.

At the other extreme of climate, millions of acres of tropical peatlands were being converted to agriculture for production of rice, taro, fish and other food; and needing answers to questions about saturation, drainage, shrinkage, oxygenation, land slippage, etc. Cornelia, with her background in geology and botany, was in a good position to help address these questions by collaborating with engineers, geologists, crop specialists and others.

Another of Cornelia’s assets was that her mom was the ultimate mentor, traveled with her to these faraway places, and shared her knowledge and experience. Mom loved fieldwork and was still sharing the teamwork when she was more than 100 years old. Cornelia returned to Iowa City and the university occasionally in the lulls between assignments, but as the years went by, fewer and fewer people knew her, and the scenes from her childhood gradually vanished.

She mentioned to Sandy and I that when she was a child little seeps and springs issued from almost every local hillside. These places are easy to locate today on the soil maps, but have almost all been tiled, ditched and drained plus, their recharge lost in the process of converting the landscape to corn and beans. She also mentioned that when she was little, she picked cranberries in a little bog near their farm, but the location was unrecognizable now in suburbia. Neither Sandy nor I knew that cranberries once grew around here. Does anyone else know about cranberries in southeast Iowa? We all lamented the loss of the natural world and the things that future generations would never experience or even know about.

Cornelia’s cranberry story makes me want to try growing a little cranberry bog or fen to see what flora and fauna it might support. But I don’t have a cold seep or spring, which would keep it damp to slightly flooded much of the year. An academic list of Cornelia’s formal publications is available on Wikipedia, but I wish she had left behind a trail of information about nature as she found it here in southeast Iowa during her childhood. Perhaps this exists somewhere, but I haven’t encountered it.