Fossil Butterflies?

Is it possible for nature to create fossils from creatures as frail and fragile as butterflies? While it doesn’t happen often, the answer is yes, under certain conditions. Our best example in the USA is at Florissant, Colorado, within 35-million-year-old shale.

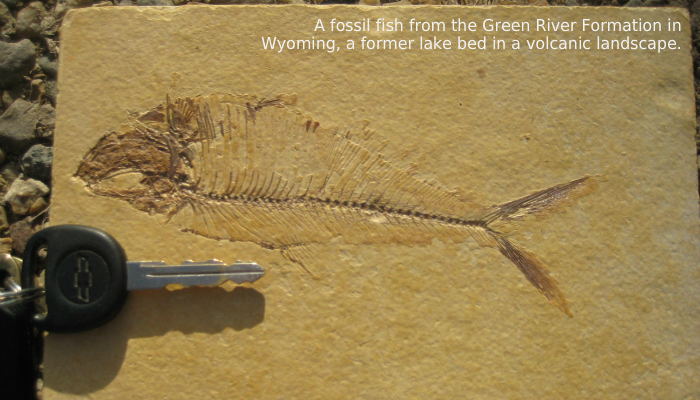

A key event here was volcanic activity with eruptions creating clouds of ash. Volcanic ash is made up mostly of powdered glass, because the eruptions are driven by gas pressure of steam and carbon dioxide, suddenly released when the earth above can no longer contain it. And like a shaken soda bottle, the foamy froth comes spraying up full of tiny bubbles, whose shells chill to glass and then shatter as they come into lower pressure zones above. Small flying creatures enveloped by the plume – birds, insects, or bats – quickly die and fall out of the sky with the ash (aircraft flying through a plume get their engines ruined quickly and can also fall out of the sky). At Florissant, some of these unlucky flyers fell and sunk into a large lake, deep enough to not be disturbed by subsequent storms.

Glass is a substance created by chilling a liquid fast enough that it doesn’t have time to form crystals. Technically it is a super-cooled liquid, and if you carefully measured a century old plate glass window, you would find it a bit thinner at the top and a bit thicker at the bottom, the glass having flowed down slower than a glacier.

This lack of crystallization also makes it chemically unstable, and over millions of years volcanic ash gradually crystallizes to clay minerals and hardens into a weak shale rock. This slow crystallization happens atom by atom, and can faithfully retain the finest detail of a butterfly, which had originally been captured in the powdered glass. It is a copy of a copy, which Xerox is still dreaming about, because it is three-dimensional and capable of detailing individual wing scales. The color patterns on an original butterfly wing are created by different types of scales and different spacing of the tiny scales, and on some Florissant fossils these are now retained, not just as scale impressions, but as different shades of brown. One can be confident about what these patterns mean when they match on both wings, match between different specimens of the same species and are similar to those of their living relatives. Also preserved in the same shale layers are many other insects, plus small birds, leaves, flowers, and fruits washed in by floods.

As of 1991, twelve Florissant butterfly species had been identified, all in families extant today, two are in modern genera and none are present living species. One species is a near relative of modern hackberry butterflies, and a species of hackberry fruits and leaves is entombed with it.

The federal government purchased a ranch that occupied a portion of the ancient lake, and in 1969 the National Park Service established the Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument to try to keep at least a few specimens in the public domain, because most had already vanished into private collections.

Elsewhere in the world, volcanic ash falling into lakes has provided us snapshots of 50-million-year-old bats (which look like modern bats), unfamiliar fish, dinosaurs with feathers, birds with teeth, plus leaves, seeds, and fruits of ancient plants evolving into those we know today. The fossil record so often shows that the plants and animals that share the planet with us have a history vastly deeper than ours, which creates obligations for us newcomers.