George Catlin’s Travelling Museum – On The Road

By 1837, Catlin had assembled his portable Indian museum and began taking it around to eastern cities. It was offered as a stage show, with Catlin onstage telling tribal stories and his adventures among them, and placing his painted portraits and scenes on easels as they appeared in the story, supplemented by the artifacts which he held up, passed around, and used as stage props. An afternoon’s or evenings enlightened entertainment for 50 cents.

Federal policy at that time was to move tribes well westward of the Mississippi River to free up good farmland for the white settlers and ultimately to have Americans in residence on the Louisiana Purchase. When Lewis and Clark passed through in 1804-1806, trying to figure out what the Louisiana Purchase had actually purchased, they followed President Thomas Jefferson’s program of trying to get tribal chiefs to visit their Great White Father. On the surface, the purpose was to show the chiefs the white man’s wonders, but the real goal was to show that it was futile to oppose Manifest Destiny.

While in the eastern cities during the late 1830s, some of the visiting tribesmen were taken to Catlin’s museum show. Catlin records a few amazing scenes in which the Indians recognized themselves or their village portrayed onstage and got excited enough to become part of the program via their interpreter who accompanied them. When Catlin was visiting Keokuk’s tribe, he of course painted the Chief first, but then the vain man (Catlin’s words) insisted that the Great Medicine Man also paint him on his horse, which was known to be the finest horse in the region.

Several years later, Catlin was doing his Indian museum show back east and told the above story, when a guy in the audience laughed loud and said that no Indian could afford that fancy of a horse. Keokuk and some of his tribesman were also in the audience. When the interpreter relayed that message to the Indians, Keokuk rose to his full height and verbally chastised the guy. Then a trader with the group stood up and said that he had sold the horse to Keokuk for $300, an unheard of price on the frontier in those days. Museums today are rather sedate places by comparison.

In 1841 Catlin published a two-volume book about his travels and experiences among the Indians, and in it made brief pleas that large chunks of territory be set aside for native people and native animals to continue their lives as he had witnessed them. It is the first proposal which I know about for national parks.

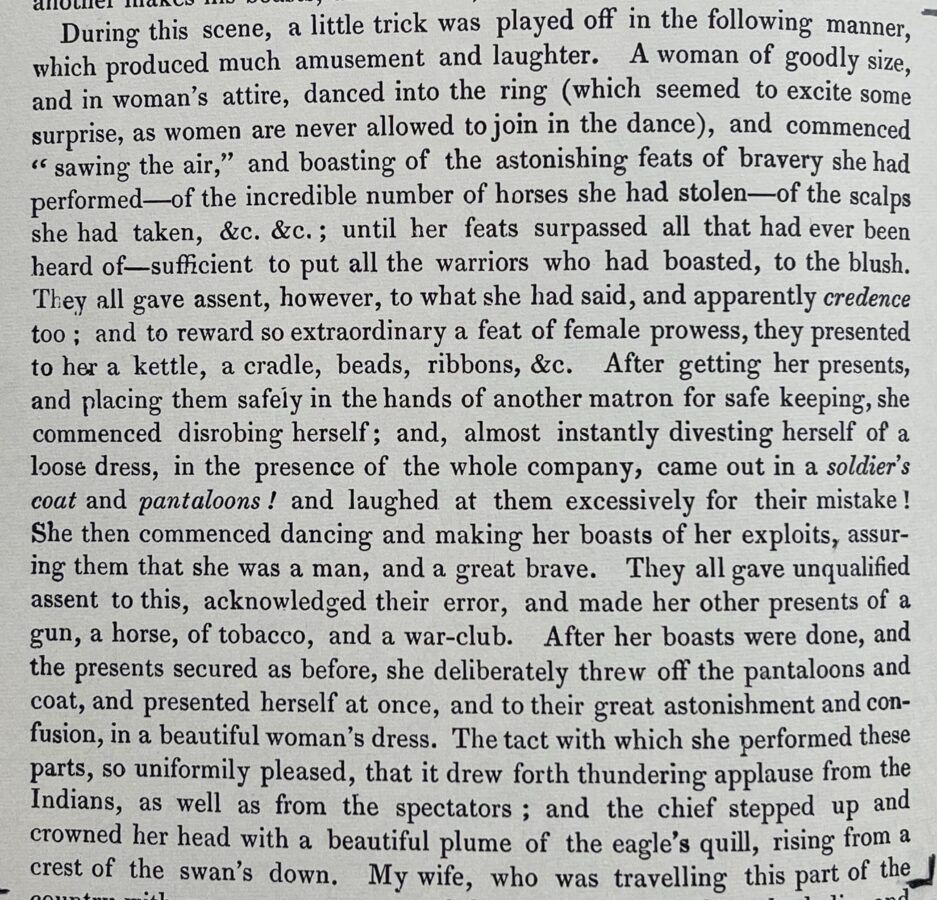

Quite to the amazement of the eastern city folks, there were liberated women amongst the tribes, some more liberated than most white women: When Catlin and his wife were at Fort Snelling (today part of Minneapolis), they spent a day watching dances and performances by visiting tribes. One turned into a charade that moved too fast for Catlin to paint and he was too caught up with it to paint anyway. In his own words, which he shared with his eastern audiences:

The travelling museum was expensive to maintain and move, so as audiences dwindled he had to move on to the next big city. Finally in a financially desperate move, he took his story overseas to the big cities of western Europe where he gradually sank into debt. A wealthy American named Harrison rescued the collection, and Catlin, by purchasing the entire package and paying off the creditors. The collection was stored in an inappropriate warehouse in humid Philadelphia, where without the arsenic treatment the artifacts deteriorated beyond saving. But the paintings mostly survived until 1879, when Harrison’s heirs donated them to the Smithsonian Institution, which gave them better care.

Catlin’s story about his travels amongst the original peoples of the Midwest are much more interesting and complex than I can relate in this little note, and I encourage you to follow up with your own readings. My main source is “Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs and Conditions of North American Indians,” by George Catlin, an inexpensive black and white 1973 reprint of his 1841 publication, by Dover, also in two volumes. The color paintings are available online.