George Palmiter Invents Green Stream Management

Following up on my recent Clear Creek blog, this is a little behind-the-scenes look at the history of stream management, which helps direct what we do here today.

George Palmiter was a railroad man in northwest Ohio in the 1960s. His hobby was “jump shooting,” which to George meant drifting/paddling down a creek, shotgun in lap, and when he rounded a bend, a couple of ducks might fly up and he might get a shot. But Dutch elm disease swept through and soon his creeks were clogged with fallen trees. Undaunted, George organized a canoe club, and armed with chainsaws and shovels they set out to make their creeks canoeable again. Given the formidable odds, George focused on efficiency, and quickly developed the philosophy to “let the river do the work.” For example, where a long log bridged the creek, he might simply make one cut through the middle and the next spring’s flood would swing the halves around, not only opening the center of the channel, but also protecting the banks from erosion. He also recognized that most of the fallen trees had been realigned by past floods and were already protecting the bank – and might only need a branch removed to clear the main channel.

By the 1970s, he was supervising local contracts to improve flow and navigation on local streams. He had also been “discovered” by outdoor magazines and professionals who recognized that his improved flow was accomplishing much of what the Army Corps of Engineers was trying to do with their awful “channelization” projects, which turned meandering streams into straight, barren, flashy ditches, at huge taxpayer expense; and moved the flash flood problem downstream so the next victim then also needed channelization.

Miami University, which is in Ohio, not Florida, tried to cookbook his procedures, but George himself was skeptical. He thought that every little stretch of a stream had its own unique combination of problems and opportunities and you needed to map it out to envision what you were doing. If the next flood took out a sandbar, where was the sand going to go?

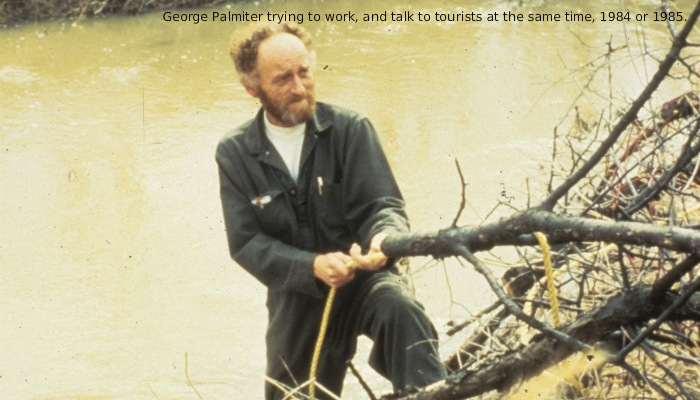

In 1983, he used his vacation to go to Washington, DC to explain his methods and results to a congressional committee, who was interested in how George’s cheapy projects could compare so favorably to Corps channelization, which could cost $200,000 per mile. He miscalculated how long that visit would take and called his boss for an extension of his vacation time. Not getting it, he quit his job on the railroad right there, and took up stream maintenance and restoration full time. A year or so later, I joined the parade of people visiting him to observe his methods and results firsthand, which I turned into a lecture and lab in my Engineering Geology class.

No, George didn’t actually invent stream management and restoration. The Chinese were doing it when Columbus accidently visited the New World. And some European countries have been using rock structures for a couple of centuries. But George is the man who worked out how Midwestern flatland riparian ecosystems could be gently tweaked to better accommodate our excesses. And he contributed importantly to the curtailing of channelization as a cure-all. The conspicuous turning point here was after the Corps had channelized a long stretch of the Kissimmee River in south Florida, they were then ordered to re-meander part of the channel.

Today this is all history; and today in states that actually value their water, stream management and restoration have continued to evolve, but that is another story for another day.