The Importance of Stored Soil Moisture

The dry spell we had mid-May to mid-June reminds me to tell you this story: When my family first moved here a half-century ago, I met some older people who had been through the “dirty thirties,” when the most important part of Oklahoma dried up and blew away – an event now best remembered by younger generations as portrayed in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. The elders told me that in that era, Iowa was the place where “it always rained – just in time.” And there is considerable documentation that while crop yields were sometimes poor, our state remained fairly stable, both environmentally and economically, without the gritty desolation of square miles turning into dust like they did in Oklahoma.

So I believed the rainfall legend for several years, until I went on a geologic field trip to Oklahoma and got a good look at their soils. The have “residual soils,” which formed over millions of years by slow decay of the underlying bedrock. On many farms the soils are about two feet think, sorta sandy, and can store an inch or so of moisture per foot of depth, which is provided by rain and snow that falls during the dormant season, for a storage capacity of 2-3 inches as they go into the growing season.

Here in Iowa, our glacially-derived and wind-deposited silts, called loess, are deep, and can store 2 inches of water per foot. Corn roots can grow to 5 feet, and trees like bur oak can go much deeper if necessary to access moisture. After winter, corn can have up to 10 inches of stored soil moisture within reach of its root tips, which is nearly one third of our average annual rainfall.

So in a good year in Oklahoma, their soil often has less stored soil moisture than in a poor year in Iowa. Consequently, I’m no longer sure that the legend of our 1930s rainfall is the real picture, and most of the Iowa survivability may have rested on stored soil moisture.

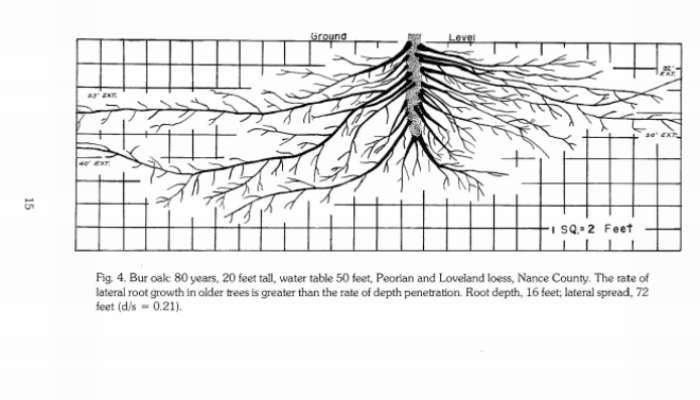

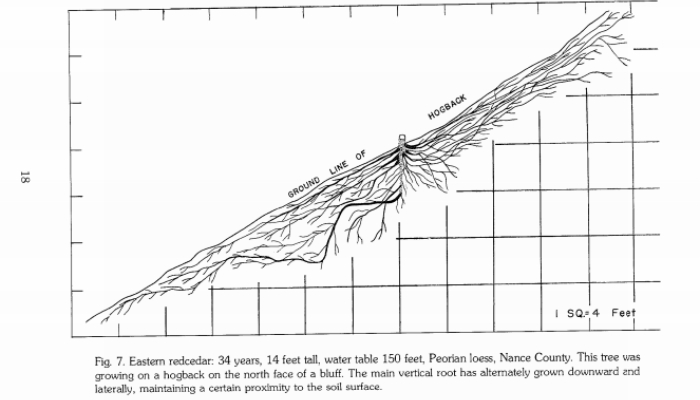

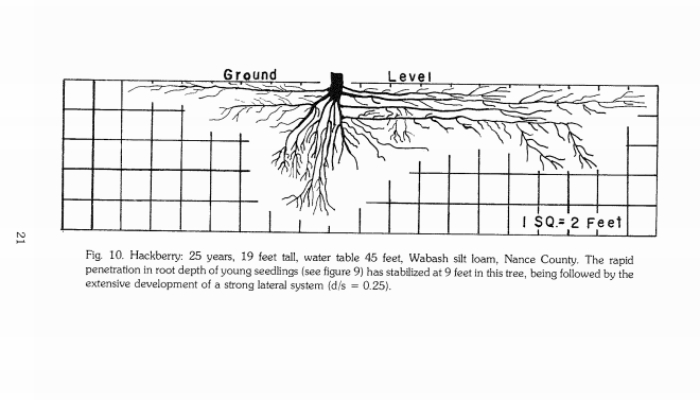

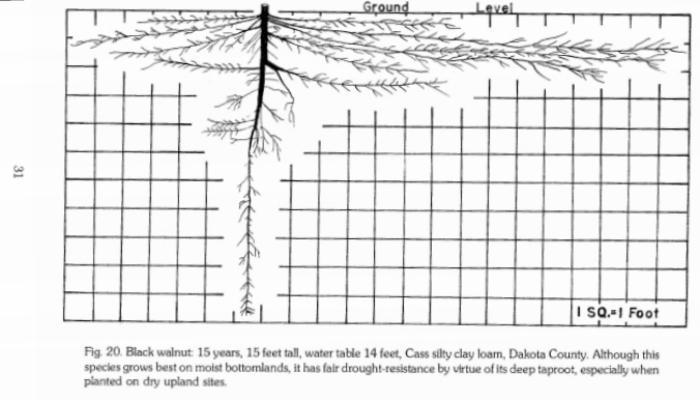

In the 1930s, some researchers focused on the resilience of trees and prairie. In eastern Nebraska, with soils similar to ours and with less rainfall, George Conda took advantage of Work Projects Administration labor to dig up 543 entire tree and shrub root cross-sections, shovelful by shovelful, to map their root systems. A sample of four of his graphics are shown for trees common to Iowa, from Nebraska Conservation Bulletin Number 37

Among his observations (page 8) is that bur oak has the deepest root structure for its height, which is what allows it to invade grasslands. Seedlings have 9-inch roots before the leaves appear, seedling roots go to 5 feet in one year on cultivated ground, 7 feet after two growing seasons, and 9.5 feet after three growing seasons. The long shallow laterals come later.

Some soil moisture spinoffs useful to us conservationists include:

- A few deep waterings of seedling trees and shrubs will encourage deeper rooting than providing many skimpy, shallow waterings.

- Oaks grown from seed in place quickly put down a long taproot and are much more drought tolerant than nursery stock, which has had its roots pruned to fit in a pot or fit into a bare root bundle. When I find one of these seedlings appearing in full sun unbidden, I try to modify the landscape plan to accommodate it.

- When I plant small trees and shrubs, I also auger or core a 1- or 2-inch-diameter hole, a foot or more deep, just uphill from each plant, and leave this hole open but covered with mulch. Then when I water, I also flood the hole with a pint or quart to soak in at depth. Over a few years, the hole gradually fills with mulch and dirt, but is still a preferred conduit for increased permeability downward, which encourages deeper rooting.

So when you are planting trees and shrubs, plan ahead for summer drought and take advantage of our deeper soils’ ability to store moisture.

Tags: Lon Drake, soil moisture, tree roots, water