Islands, Cores, and Corridors II: 1992-1994

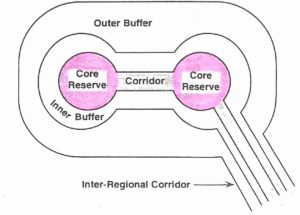

An idealized core/corridor/buffer concept.

Until 1992 there was no organized concept plan available to deal with the realities that most conservation lands were biological islands, and subject to all the problems of isolation, inbreeding, and extinction. But in that year the Cenozoic Society published the Wildlands Project, a special issue of the magazine Wild Earth. The basic concept offered therein was that you deal with these islands by treating them as core reserves managed specifically for large native carnivores, and then link the islands with corridors so that some gene flow is possible between them. Ideally there would also be buffer zones around the cores and corridors, thinly populated by humans, in semi-natural landscapes used for logging,

grazing, oil fields, fishing, etc.

In many landscapes these corridors will be riverways, swamps, shorelines, or rocky ridges. The design emphasis is on large carnivores because these need the largest areas, and they also usually exert top-down management on their ecosystem (the wolves in Yellowstone are a well-known example today, although few were so aware of it in 1992).

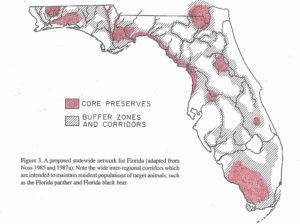

So what does a core and corridor system actually look like in the real world? Here is Florida, avoiding the cities and the built up coastlines and the denser concentrations of people (idealized concept and map published in the Wildlands Project special issue):

Most of the 1992 Wildlands Project publication is like the Florida example, a series of sketch maps of specific examples, each accompanied by a couple of pages of text. Places they selected include an Adirondacks Wilderness Reserve System, a Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, a Blue Ridge – Smokey Mountain Provence, a Southern Rockies Ecosystem, a Northern Rockies Bioregion, plus several places outside the United States.

This vision, of course, raised far more questions that it answered: for example, how much habitat of what quality is actually needed to support a specific top predator, and how shall it be managed? Enter Saving Nature’s Legacy, in which Reed Noss and Allen Cooperrider compile, summarize, and interpret a significant portion of the North American literature to address these questions. One might expect such a hefty compilation to be about as exciting as a telephone directory, but in fact, the authors develop storylines and keep them interesting by dwelling only briefly on general concepts like island biogeography and returning quickly to practical questions for specific areas. Here is where you find out why we need large areas managed as large units, if we are going to slow the rate of species loss and keep ecosystems functional. Here is where you get explicit guidelines on inventorying biodiversity, selecting areas for protection, designing reserve networks, monitoring, priorities, management details, etc. However, be prepared to do some heavy-duty reading, because the content is equivalent to taking an advanced university course. Documentation is thorough and the references cited occupy 45 pages of small print.

I’m not the only one who was impressed by these two publications. The core-and-corridor concept immediately became a framework of reference for many other researchers. Within 2-3 years it had started to creep into the planning for public agencies, like U. S. Fish and Wildlife, and for non-profits, such as The Nature Conservancy.

Even though now a quarter-century old, the vision these two publications offered has become the operating instructions for conservation across the United States and in much of the rest of the world. Next week let’s take a look at a couple of modern examples.