Islands, Cores, and Corridors III: Today

Corridors are proving to often be more difficult to create, manage, or preserve than cores because they so often involve many different landowners. So it may take only one uncompromising person to effectively block the whole project.

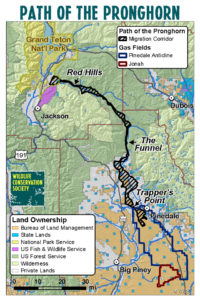

But it can be done, and a fine example for preserving/creating one is the Path of the Pronghorn in Wyoming. This is a specific route that has been utilized by a select group of antelope for their annual migration, possibly for the past 6000 years. About 80 miles long, in modern times it crosses a hodgepodge of federal, state, and private property. Some segments are a mile wide, but one section narrows down to about 100 feet. Early attempts to market this preservation concept in Washington made no headway, even though much of the land is federal and managed by federal agencies. But when pitched to Wyoming governor Dave Freundenthal, he immediately bought into it and had the leverage to start the wheels turning. It was still a long haul getting landowners to buy into it and a half dozen agencies to cooperate, but in 2008 federal protection of this corridor was granted.

But it can be done, and a fine example for preserving/creating one is the Path of the Pronghorn in Wyoming. This is a specific route that has been utilized by a select group of antelope for their annual migration, possibly for the past 6000 years. About 80 miles long, in modern times it crosses a hodgepodge of federal, state, and private property. Some segments are a mile wide, but one section narrows down to about 100 feet. Early attempts to market this preservation concept in Washington made no headway, even though much of the land is federal and managed by federal agencies. But when pitched to Wyoming governor Dave Freundenthal, he immediately bought into it and had the leverage to start the wheels turning. It was still a long haul getting landowners to buy into it and a half dozen agencies to cooperate, but in 2008 federal protection of this corridor was granted.

Sometimes other brands of politics interfere with connectivity. Both jaguars and ocelots are documented to be present today in northernmost Mexico, and they were originally present in Arizona and New Mexico. But The Wall is becoming an increasingly impermeable barrier to their migration northward, and the present federal plan is to make it more impermeable.

Sometimes other brands of politics interfere with connectivity. Both jaguars and ocelots are documented to be present today in northernmost Mexico, and they were originally present in Arizona and New Mexico. But The Wall is becoming an increasingly impermeable barrier to their migration northward, and the present federal plan is to make it more impermeable.

In 2018 the Wildlands Network finished mapping potential cores and corridors for the eastern United States, and like our Florida example last week, there are a lot of options and alternatives.

Many of the core areas, in green above, exist with a fair amount of internal continuity. Some of the corridors, in yellow, are riverways and rocky ridgetops not needing too much physical management to be useful, but most are private property.

The Appalachian Trail is already an animal corridor over much of its length and is shown in red on the above map. Because it is already there, the Wildlands Network has gone on to identify seventeen areas along or near the trail that have special value for conservation and are perhaps not too difficult to link to the trail. They are now working up public programs to generate local interest in integrating these areas.

Core and corridor planning has largely bypassed the Corn Belt due to perceived lack of opportunity , even though surrounded by the Boundary Waters, the Ozarks, Shawnee Forest, and the Sand Hills. The combination of roads everywhere, plus disinterested/hostile governments make it more of a challenge.

The animals do send a message. About three decades ago, Barb and I were driving on Rohret Road, and imagine our surprise to encounter a moose only a mile from our house. Every few years a bear will wander south from Minnesota into Iowa, usually following the wooded blufflands along the Mississippi. On the rarest of occasions, a mountain lion will appear somewhere in the state and they are so secretive that we really never know where they are coming from or going to. In the past few years several wolves have been shot by coyote hunters in northcentral Iowa, probably loners drifting south from Minnesota.

Iowa has four possibilities for linking into a future core and corridor system with other Midwestern states. The Loess Hills are a mosaic of prairie, woodland, grazing, and row crops. The Mississippi River blufflands are too steep for row crops and in some places even too steep for grazing by cattle. Some segments of our creeks and rivers still offer habitat possibilities, although the flooding with silty herbicide-laden water leaves only a few species able to tolerate it, resulting in stands of mostly silver maple and little else. The wild card might be our trail systems. They are very narrow and designed to connect cities rather than habitat cores. But they are mainly used by people during the day, and the larger critters are more often abroad by twilight or at night. And there is often a fringe of habitat along the edges, so they have some possibilities as wildlife corridors.

In more progressive states, many of the little pieces of land, which had been conserved and upgraded, are being assembled into more functional core and corridor ecosystems, serving both wildlife and people. How and when this comes to Iowa depends on us conservationists.