King Coal Visits Iowa

This winter season, some of my blogs are going to venture into Iowa energy, sustainability, and links to the environment. Today let us consider a bit of the history of King Coal visiting Iowa.

Geologically, coal swamps get off to a slow start forming, with decay initially outpacing accumulation of dead plant remains, so the main deposition is fine clay washed in from the surrounding landscape. But as tannins build up, decay slows and peat begins to form, slowly morphing to lignite and with deep burial and much time, transitions to bituminous coal. Thus many coal seams have an “underclay.”

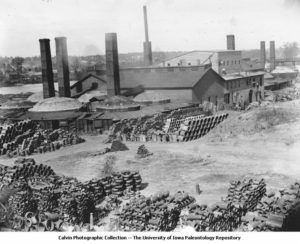

At What Cheer, Iowa, the underclay was thick and of ceramic quality, so that in the pioneer era a single shallow mine yielded both good clay and the coal to fire the kilns used to produce chimney tiles, drain tiles, bricks, building construction tiles, and a variety of pottery products. Eight large walk-in kilns were in use. This produced employment and wealth for the town, allowing them to build the opera house of high enough quality that Jenny Lind came from New York City to sing.

photo from UI Calvin Collection – caption: The Des Moines tile works

The factory remained in production until the late 1960s. When I visited the abandoned What Cheer mine around 1973, the kilns were still intact, and the sheriff checked me out, making sure I wasn’t another hippie trying to move into a kiln. The Iowa Geological Survey calculated that around 1900 there were 380 such brick and tile works around the state, burning coal to fire clay products, mainly drainage tile.

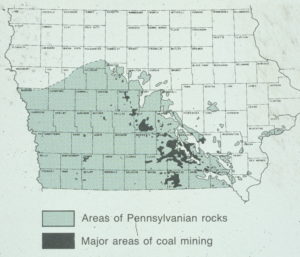

Coal mining areas in Iowa.

Iowa was originally endowed with a great abundance of little coal seams. A few were located near the Mississippi River along the southeast edge of the state. And they were abundant in south-central Iowa.

There were coal seam outcrops along the major rivers in this area and rarely, people digging a house basement hole would encounter a seam and they could have their own mine in the cellar, right beside the furnace.

As the west became developed, railroads pushed across Iowa, in part because of flat ground, and in part because Iowa was the last place to fuel up with coal when heading westward and the first place to fuel up coming back. From about 1875 to 1900, Iowa produced more coal annually than any other state. We think of Iowa as a state of farmers, but economically and socially, we were also a coal state. And there was often no difference; families often farmed in summer and mined in winter. John L. Lewis was an Iowa coal miner who moved on to Appalachia to unionize the coal industry there.

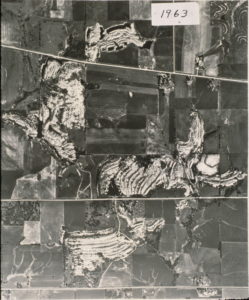

A 1963 aerial view of strip mines in south-central Iowa.

Acid drainage running out of a collapsed underground mine in south-central Iowa.

New gullies in an abandoned strip mine “reclaimed” only a decade before, in south-central Iowa.

Shallow workings were initially widespread in south-central Iowa. Some were just pits called “dog holes,” others were tunnel systems propped up with timbers. These were gradually replaced by, and often enveloped by, strip mining, which turned the entire landscape upside down, with the soil on the bottom. No one seemed to be concerned about the landscapes being ruined, there were always more acres of prairie to plow nearby.

The environmental questions for Iowa 50 years ago were:

1. Can anything be done to mitigate hundreds of abandoned strip mines?

2. Can future mining be done without creating these environmental disasters?

Some answers next week.