Land Easements Become Conservation Easements, Yesteryear

Conservation easements as we know them have their origins in British law and traditions centuries ago, when the landscape was entirely in large estates owned by nobility. The people who actually lived and worked there were paid little or nothing, but often had easements allowing them to build homes, garden, collect firewood, graze their livestock, etc.; although deer hunting and salmon fishing were reserved for landowners. Deforestation was already a recognized problem by the 1300s, and one of the conservation rules of that era stated that an easement holder could not cut a tree if he walked in a circle around it and could see a stump in any direction. Even today in blue-collar England it is quite slanderous to call someone “hedge-born” because it implies that their family has been so worthless for many generations that nobility has never granted them an easement to even build a shanty. This is linguistic carryover from past centuries when estates were bounded and divided by deep hedgerows, maintained as fences by professional pletchers who wove the brambly tangle to be cattle-proof. In southern England with its mild climate, the homeless could survive in these sorta inadvertent conservation corridors, eating from its bounty of fruits, nuts, small animals and birds, supplemented by occasional poaching of a chicken or lamb and building little stick fires to stay warm, brew herbal tea and cook; and living in brush shelters. Pigs were difficult to contain in a pletched hedgerow, and landowners learned that a reliable sty warden could also become a reliable land manager, while linguistically yesterday’s styward became today’s steward.

Land easements came to Iowa with the pioneers. The state had been surveyed while the last large tribes of natives were being driven off and/or bought out. Early white farmers granted road easements straddling their mutual property boundaries. Exercising eminent domain was hardly necessary, because most owners were glad to have a real road go past their farm, some even offering to help maintain it, if they were selected to be on the main route to town. So even today, most rural landowners still own title to the center of the adjacent road, while the county holds an easement, which allows them to control and manage the right-of-way for purposes of transportation and public safety. The landowner gets the tangible benefit of paying no taxes on his ROW strip, typically a half-chain (33 feet) wide. Squabbles pop up sometimes regarding whether a county can prevent a landowner from stringing up an electric fence in the ROW and grazing livestock on his property; whether an owner can plant shrubs on the backslope; and whether the state DNR actually has authority to allow trapping and hunting by others on someone’s ROW. On some farms, these weedy/brushy strips are about the only habitat remaining.

Railroads were frequently run through Iowa on land easements and the contract often stated that if the ROW were abandoned as a transportation route, then the strip would revert to the adjacent landowner, who sometimes retained title. Today, rails-to-trails advocates claim that bikes and walking also constitute a form of transportation and are a legitimate conversion; while adjacent landowners are anxious to either get paid for their title or plow under the ROW. Some of these railside parcels are now the last prairie remnant or last patch of habitat in their local area, and sometimes these patches collectively form a conservation corridor. Court cases about these uses still occur, and the outcomes not only depend upon the exact wording of the original 100 or 150 year-old easement contract, but upon precedents, subsequent state laws, jury selection, lawyer’s talents, etc.

Modern conservation easements benefit from these older examples, by being able to better anticipate future situations and write up a sufficiently comprehensive agreement to preserve the interests of both (or all) parties. According to The Nature Conservancy, the first modern American conservation easement in the US was implemented in 1891 in Boston by a Massachusetts land trust. This legal option was subsequently very rarely used until 1976, when Congress modified federal law to allow landowners to claim the value of the donated easement as a tax deduction. The tax details have been shuffled around several times since then, changing the dollar amount one can carry over into subsequent years, changes in real estate tax, and other aspects of how the deduction can be implemented.

As the 1976 tax benefits came to be understood and appreciated by conservation-minded landowners, so did land trusts come to realize that their budget would stretch further using conservation easements, compared to investing in outright ownership. This new tax law was a factor in creating the Johnson County Heritage Trust (now Bur Oak Land Trust) in 1978, because while the law now allowed the possibility of tax relief, the owner still needed someone responsible and permanent to donate the easement to.

This legislation did prove to be a headache for the IRS, because “conservation” in not a crisply defined term, and a great variety of land-based schemes and scams were created to avoid taxes. More than anything else, the frauds led to the national program for accreditation of land trusts, in which they must document having all their ducks in a row to actually accomplish genuine conservation on parcels for which they accept responsibility, on a permanent basis. Bur Oak Land Trust went through this procedure and was officially accredited in 2013, and is currently going through reaccreditation.

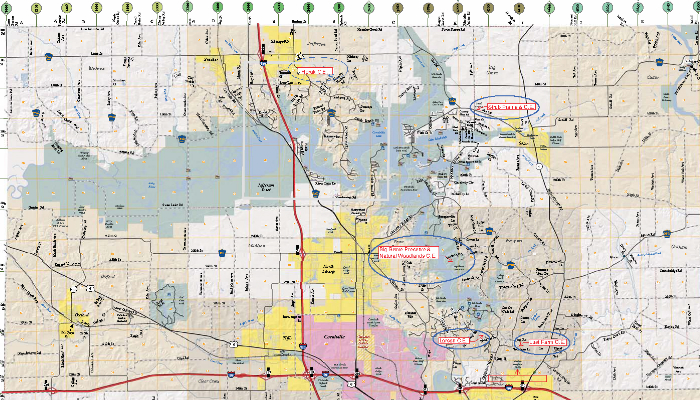

Next week we will visit what actually goes into a modern conservation easement. (Photo shows the conservation easements Bur Oak Land Trust currently holds.)