Large Meteor Impacts, Part III: Iowa

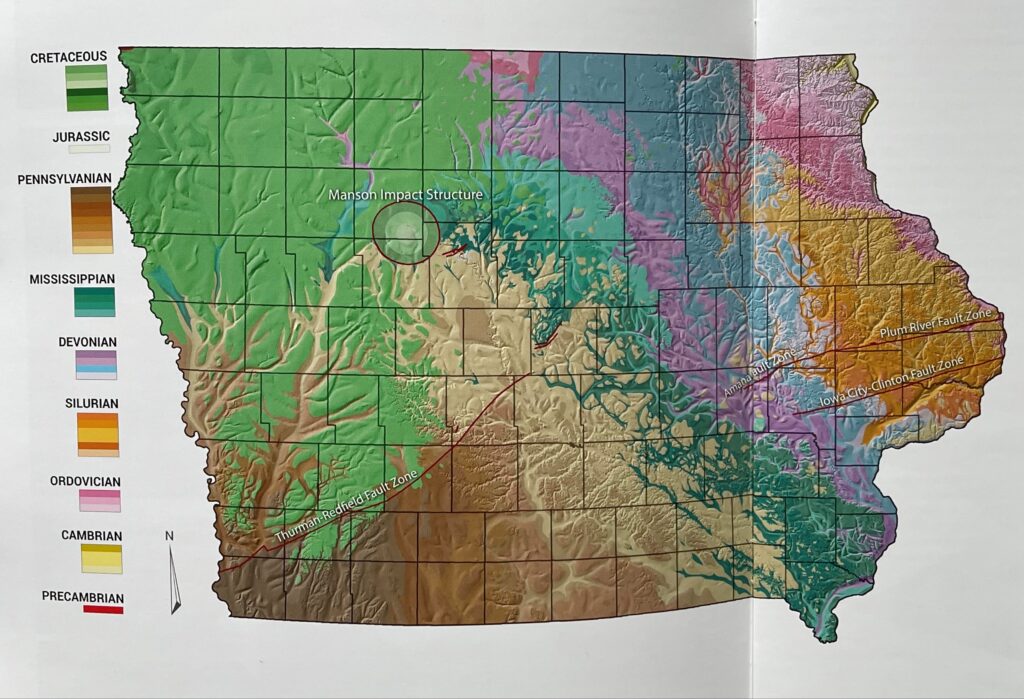

A recent map showing the location of the Manson, Iowa, impact structure within red circle/Iowa Geological Survey

A century ago, well-drillers in the vicinity of Manson, Iowa, knew that there was something different about the local bedrock and its groundwater. Instead of the usual limestone, sandstone and shale of the northwest part of the state, the chunks that came up out of the drill hole were igneous or metamorphic, often loosely called granite.

The early drilling method was with a “cable tool,” a heavy iron bar on the end of a rope that slowly pounded its way through rock by simply being raised and dropped repeatedly, with occasional breaks to pour in some water and bail out the slush and chips. Sometimes in the Manson area, the iron bar would drop and get wedged in and be difficult to retrieve, and the drillers thought that they were pounding their way through a collection of loose blocks of rock which could twist and move a little and capture their iron bar.

Most wells in Iowa produce groundwater which is hard or very hard because limestone is everywhere. This is a fairly soluble rock, which can dissolve so extensively as to produce caverns. But the groundwater around Manson is soft because the granite bedrock is made of nearly insoluble minerals like quartz and feldspar.

The origins of this strange rock was long a mystery because like the surrounding area, the rock’s surface has been planed by glaciers and then buried under thick glacial sediments, so the landscape above it is just more flatland Iowa. Collectively, the novel water wells delineate a circular area of about 23 miles diameter. But about a half-century ago, with growing knowledge about meteor impact structures, plus greatly improved drilling capability, with new geophysical scanning techniques available it became clear that this site was the lower uneroded remainder of a meteor impact.

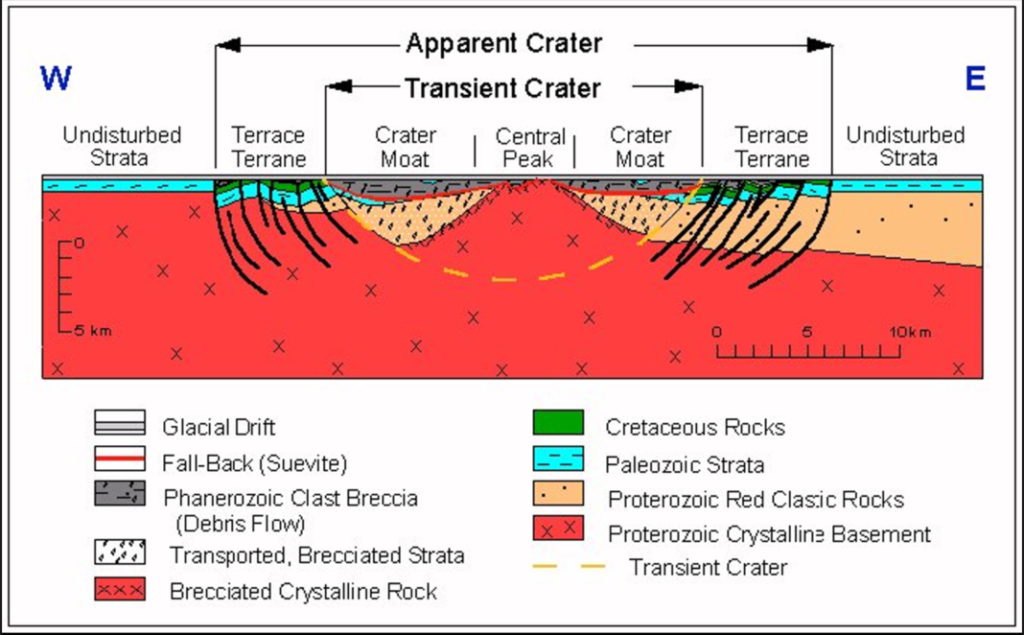

Today, we know that the rebound breccia of mostly crushed basement rock is about five miles deep, and it contains the shocked quartz characteristic of impact. The event dates 74 million years ago, and energy modeling suggests a meteor about 1.5 miles diameter.

The Iowa Geological Survey (IGS) has long maintained a library of drill hole profiles created from samples of chips sent in by water well drillers. When first received from the drillers, these grubby little labeled bags of gritty mud don’t look like much. But after careful washing and with scrutiny under the microscope, tiny fossils and distinctive rock chips reveal which geologic formations they came from. In their annual report for 2019-2020 (page 7), the IGS mentions that their Geosam database is an online catalog of over 90,000 drilling records, and more than 23,000 have been studied and portrayed as strip logs, which are vertical profiles of the geology at that site.

Some 20 years ago, geologists upgrading this library noticed that a shale layer was present at-depth in the Decorah area, which was not present within the same package of rocks in the surrounding formations. Follow-up research demonstrated that 470 million years ago a meteor crater 3-4 miles wide had been blasted into the bedrock beneath a shallow seaway. The water had returned, and mud, later compacted into shale, had gradually filled the hole. Beneath the shale, a broken breccia of crushed rock is present containing shocked quartz. Later, aerial surveys of electrical resistance outlined the dimensions of the buried crater.

Our lunar surface shows scars of many meteor impacts young and old, large and small. Planet Earth is a bigger target with a stronger gravity field, so we should not be surprised to have taken many hits. But erosion is active here. Whole mountain ranges can come and go in a mere 200 or 300 million years and deposition can bury the evidence even more swiftly. The subduction portion of plate tectonics gobbles up vast areas of seafloor so quickly that the evidence totally disappears.

So here in the stable middle of the continent, with mountain ranges growing and eroding on both sides of us driven by plate tectonics, we should not be surprised that Iowa does have an impact record surviving.