Nothing to Do? Design a Species

Populations of plants and animals are constantly attempting to adapt to the shifts and changes in their environment. For example, within a decade after Roundup herbicide came into general use in the Midwest, Roundup-ready weeds began to appear. As farmers increased the concentration to kill them, the weeds kept pace, finally reaching tolerance levels that began to harm Roundup-ready crops. The chemical manufacturers began to add other herbicides, like Dicamba, to their potions, and today subsequent populations of superweeds have begun to adapt to these mixes also.

Weed populations in annual crops are mostly annuals, giving them the advantage of a new generation each year, some of which are slightly better adopted to herbicides. Field corn breeders help keep the odds in their favor by growing a summer generation in the Midwest and a winter generation in Hawaii, giving them 20 generations to manipulate in a decade.

Likewise, given enough generations with some survivors, many species can gradually change to adapt to their environment. Some of these resulting adaptation patterns in animals are easily observed by us, including for example:

-

- Prey species often have their eyes on the sides of their head for wide-field vision (deer, rabbits).

- Predator species often have their eyes facing forward for crisp binocular-stereo vision (hawks, cats).

- Species with good night vision have large eyes to gather more light (owls, lemurs).

- Carnivores have pointy teeth up front for grabbing prey and tearing meat (wolves, alligators).

- Herbivores have blunt teeth up front for crushing and gripping vegetation (horses, deer).

- The fastest birds have swept-back wings like a jet plane (falcons, swallows).

- The most maneuverable birds have short wings that beat rapidly (hummingbirds, woodcock).

- Soaring birds have long wings to capture gentle breezes (albatross, vulture).

- Mammals that swim fast are very smooth and streamlined (orcas, seals).

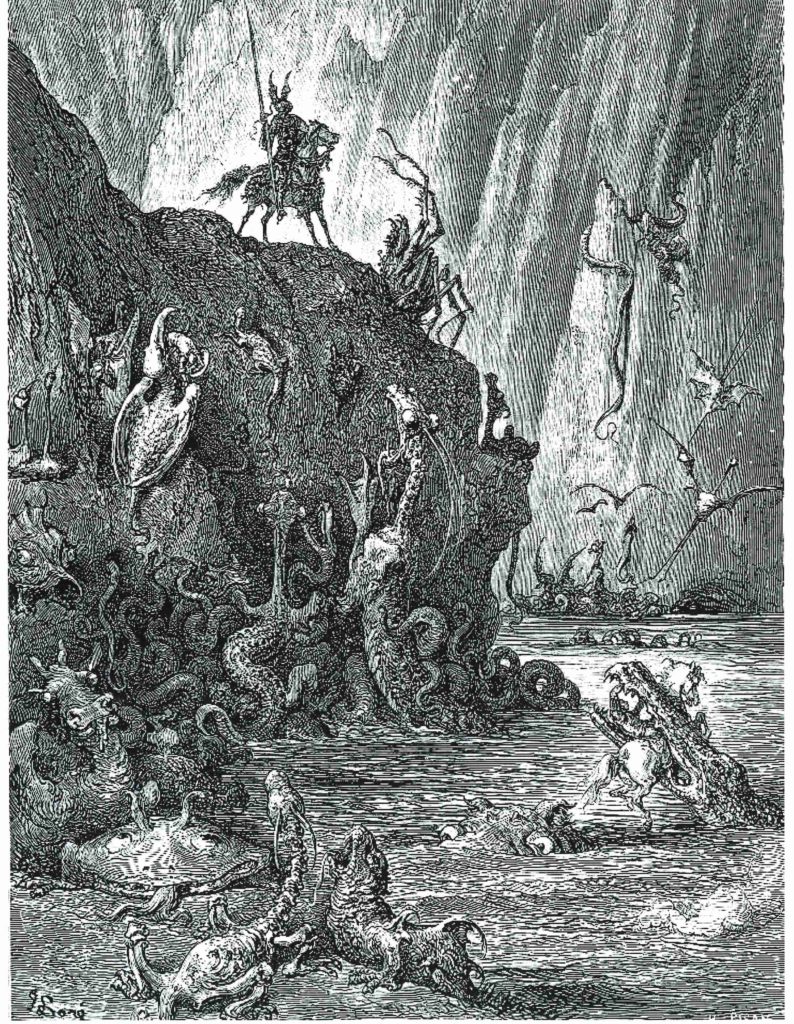

Now consider Gustave Dore’s wild scene of imaginary species:

Today, take each Dore creature individually and use the above types of criteria to figure out its role in habitat. What does it eat? How does it hunt? Does it migrate? Can it hibernate? And what species of real-world critter might it have developed from? What environmental circumstances might have nudged a population to develop like that? Or maybe such critters have already developed in the past, do any of them look like species we know from the fossil record?

After you have considered the above questions, try moving on to creating your own species. Create some imaginary niche and then design the critter that could specialize in thriving there. For example, how about designing a bird that walks on waterlily leaves and spears minnows with its beak? Or how about creating an amphibian that lives in an underwater burrow and sneaks into alligator nests to steal eggs? Make a drawing of your critter in their niche.

Enjoy your summer!!

Tags: kids and nature, kids in nature, Lon Drake