Our Ecosystem Moving North

Back in the 1970s, I started taking my kids canoeing in the Boundary Waters Wilderness of northern Minnesota. Driving north from Minneapolis the cornbelt landscape begins to take on a more northern flavor, with the deep soils giving way to shallow bedrock; the muddy streams becoming clear and cobbley; and corn, beans, oak, and big bluestem being replaced by pine, birch, aspen, and waterlilies.

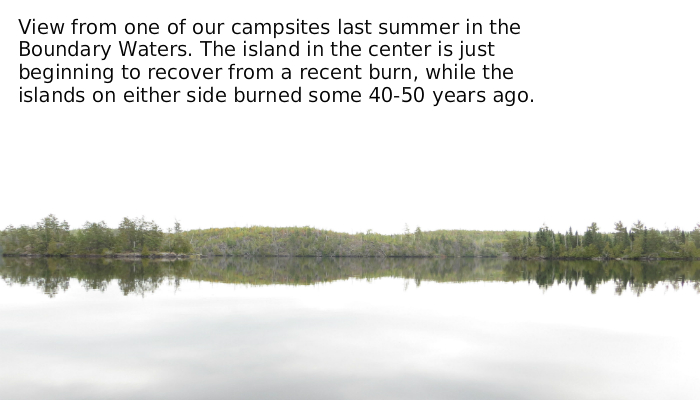

The news today is that within this broad transition zone the vegetation is shifting. At the southern edges of their range, the northern species, like aspen, are not reproducing as well; and the southern species at the northern edges of their range, like oak, are doing better than before. These changes are measured at the seedling and sapling stages, but they are the forests of the future. The evidence points to climate change as being a big factor, possibly the only factor. In overly simplistic terms, our Midwest oak-savanna ecosystem is creeping northward into the southern edge of the Great Lakes ecosystem.

So how do we view this, or turn this, into an opportunity for conservation? One of the large-scale uses of the transition zone is regularly harvesting the fast-growing aspen for pulpwood, which gives the land part of its market value. But with aspen not doing so well with today’s hotter summers and skimpy winters, the land’s market value declines, unless there is a nice lake nearly to enhance its tourist value. Meanwhile, here in the Cornbelt, savannas were exterminated so early in pioneer days that we today didn’t even really know what a savanna was until Steve Packard sharpened the focus in the 1980s. And viewed long term, the market value of corn land is an order of magnitude greater than aspen land.

So now there is opportunity to purchase common and comparatively cheap aspen land in the southern transition zone and nudge it toward becoming oak savanna, moving that ecosystem out of just the deep soil cornbelt and keeping up with the climate shift. This general approach is most commonly labeled “assisted migration” but a dozen other terms have been applied, sometimes with somewhat different spins on the interpretation.

The Nature Conservancy has already begun this experiment and so have a few private individuals. It is far too early to evaluate the outcomes, given the slow growth of trees, the complex lifestyle of terrestrial orchids, the role of fire, the animals who eat and who spread seed, and dozens of other factors, which can only be evaluated over decades. One approach is to simply manage what evolves there, selectively thinning the northern species. Another is to actually plant more of the savanna species and assist their migration.

And we, here, have several roles to play. One is maintaining the reference parcels for what constitutes an oak savanna, how it behaves, how to manage it, etc. Two is providing habitat for migrant birds, who are heading for the Great Lakes ecosystem in spring, and then to the tropics in autumn, and must pass through the Cornbelt, running the gauntlet of rather skimpy little islands of habitat in the sea of corn and beans. This makes our small parcels of preserved and created habitat all the more important.