Quaking Aspen

There are two species of aspen in North America and both of them live in eastern Iowa. The two are easily distinguished by their leaves. The quaking leaf is often quite round with nearly smooth edges and the bigtooth leaf is more elongate with somewhat jagged edges.

In the western states – the more arid parts of its range – quaking aspen favors the cooler, shadier, moister microclimates of north-facing slopes, canyon bottoms and ravines. Both aspens are very clonal. When you see a little grove of young aspen saplings behind an Iowa fence and creeping out into the pasture, they often are all one tree connected at the roots. Easy clues that this is the case are when they all leaf out together in the spring and then turn yellow simultaneously in autumn.

In the North Country of New York, the aspens are common trees because they regenerate so quickly after fire or clearcutting. Their elaborate root systems often sprout promptly, and their fine wind-borne fuzzy seed blows for miles and loves to sprout on bare mineral soil. Vast quantities of aspens are clear-cut for pulpwood in Canada, with natural regeneration providing a 40-50-year “rotation.”

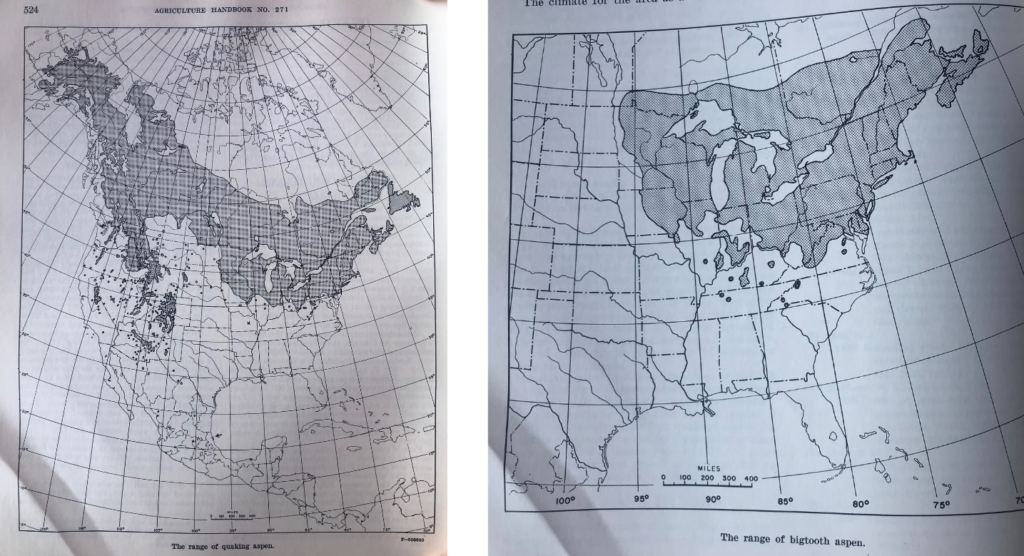

From left, quaking aspen and bigtooth aspen range maps from Gary Hightshoe’s encyclopedia book “Native Trees Shrubs and Vines for Urban and Rural America,” 1986, Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Wildlife such as deer, moose, elk, rabbits, hares and porcupines generally favor the regenerating young trees of clear-cuts and burns. Plus, grouse eat the buds all winter. The connoisseur of aspen, however, is the beaver, and mountain men used the tree as their guide to place their trap-lines. To us humans, the inner bark tastes quite bitter and the early white settlers consequently tried it as a substitute for bitter quinine, which comes from the bark of a Peruvian tree.

The leaves of quaking aspen hang on long, flattened and flexible petioles whose plane is at right angles to the plane of the leaf blade. Consequently, each movement of the leaf causes it to twist, giving it a constant flutter in the most gentle breeze and making a distinctive sound. Back East, where I grew up, the Onondaga people called this tree nut-ky-ee, meaning “the tree-that-talks,” referring to the constant murmur of the leaves. The bigtooth aspen and its cousin, the eastern cottonwood have less flattened petioles and are more taciturn.

Aspens are part of the large tribe which includes willows and poplars. They are all rather promiscuous and a number of natural hybrids are known, and many cultivated crosses have been made. But over generations, most of these fade away and do not become part of the native landscape. My personal hypothesis, as yet unadorned by facts, is that bigtooth aspen is perhaps a stable hybrid between quaking aspen and eastern cottonwood, getting its general growth form from its quaking parent and its leaf shape and range limitations from its cottonwood parent.

From left, quaking aspen leaf, photo by James St. John, Creative Commons, and bigtooth aspen leaf, photo by Esagor, Creative Commons.

Aspens may seem kinda wimpy compared to old oaks or hickories until you remember how clonal they are and that the whole grove you are walking through is, in fact, a single tree. The largest I’ve read about is a grove on a Utah mountainside, which covers about 100 acres and contains an estimated 50,000 stems if you included all the small ones. With modern DNA-type testing, the clonal hypothesis for some of the large groves is now beyond question.

The follow-up question is how old these huge clones might be. One opinion, widely shared, is that some of the western mountain clones started growing at the end of the last ice age and could be 10,000 years old. So far, there seems to be no way to actually measure the age of an organism which keeps renewing itself so completely.

Aspens may not get much respect or even get noticed here in Iowa, but as you work your way northward it plays an increasingly important role. And if you go far enough north, it can become your only arboreal companion, providing shade, firewood and conversation at your camp. And if you split your canoe paddle in the rapids, you can trim out a replacement from an aspen trunk with your axe. The big bears reach up high to groove the smooth bark with their claws, and if these are still damp with sap or show no signs of healing, maybe this is not such a good place to camp. A most useful tree.