Record Rains

Two decades ago I was still teaching Engineering Geology, with several weeks of lecture, lab, and field trips devoted to dams and floods. The two themes were packaged together because heavy rainfall is a frequent driver of dam failure when design is marginal; and failure of dams, both natural and manufactured, have produced some notable floods. With rainfall, the intensity and duration are as important as total amount. For example, locally in 1993, the frequent rains were well-spaced and gave upland dams time to drain away much of their excess before the next storm arrived. But along the Iowa River, it was a disaster because the upland excesses were cumulative down below.

Our most current example of a rainfall disaster is Hurricane Harvey, which has been giving Houston repeated waves of rain too frequently to have any drain-away opportunities. Buildings, bridges, billboards, and floating debris also clog the exit.

Houston is built in a broad depression and one could hardly have found a worse location for the convergence of floodwaters. Sims Bayou drains in from the south; Keegans, Willow, and Brays from the southwest; Horsepen, Longham, Bear, and Buffalo from the west; White Oak and Cole from the northwest; Garners, Williams, Greens, and Halls from the north; and Lake Houston and Sheldon Reservoir from the northeast. And all this input is trying to drain out to the east through a suburb appropriately named Channelview.

This was a “disaster waiting to happen.” The disaster is an overheated Gulf of Mexico pumping soggy air inland.

Naturally, in my class, the topic turned to the most intense/prolonged rains known to occur. A few references to compare to include Iowa City average annual rainfall of 32 inches, and the record – in 1993 – was 63 inches; while in the Houston area, maximums were 37-56 inches, in only a few days, in different parts of the city.

But these numbers pale when compared to extremes world-wide. A record-holder for one combination of duration and intensity is Cherrapunji, India, often directly in the path of waves of incoming monsoon storms. Between June 24 and July 8, 1931, 189 inches of rainfall were recorded. That’s averaging a foot per day for half a month!!!

So why do we care what happens in India? Let me make a comparison.

In the southeastern US, the warm and humid Gulf air starts pushing northward in March and April, reaches its northern limits in July and August, and is then gradually pushed back by arctic air until late winter. This seasonal north-south flow is classified as a monsoon, created by the same geographic situation as in India, which is a continent facing a warm ocean to its south. Our monsoon is just not as intensely developed as the famous one that overrides India annually, because our Gulf of Mexico does not get as hot as the Indian Ocean – as it is closer to the equator. And because the warm Gulf Stream tracks up our East Coast, large storms can continue to feed off the Gulf Stream there.

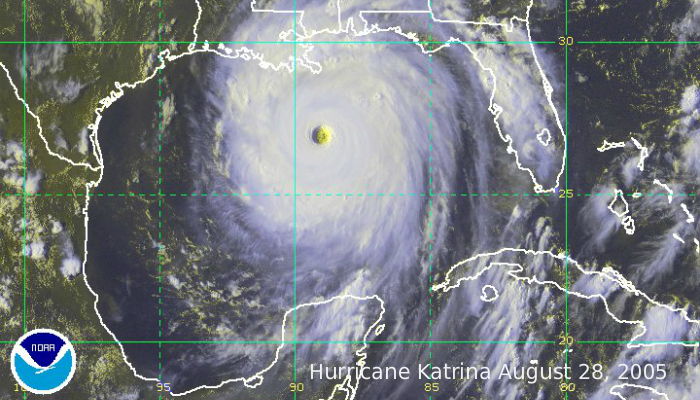

Could it be worse in Houston in the future as climate change continues to crank up? The parallels with India’s monsoon – plus our failure to even slow down the rate of climate change – suggest that this is pretty much inevitable. Katrina, Sandy, Harvey…