Ring of Fire

Bur Oak Land Trust blogger Lon Drake recently wrote a fine commentary titled Why We Burn, What We Burn, When We Burn, How We Burn. It concluded with this sentence: “So when you are responsible for a fire, think through your goals, including how the animals will respond, and factor that into how you burn and when you burn – and even if you burn.” The emphasis on the last phrase is mine.

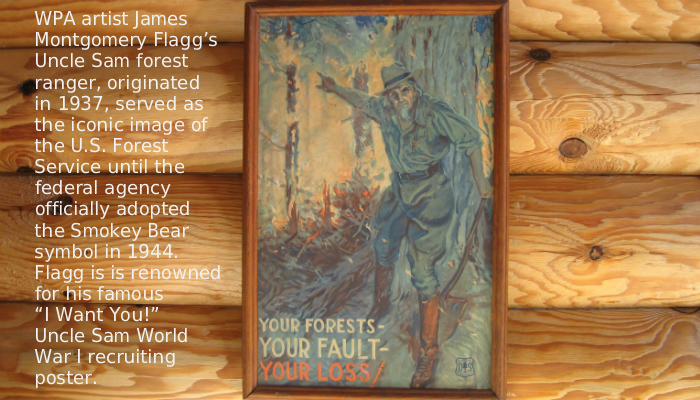

I was trained at the U.S. Forest Service Regional Fire School and smoke jumper base at Idaho City and worked four summers (1961-64) on fire control in the Boise and Payette National Forests. At 2.9 million acres, the Boise was then the largest national forest in the lower 48 states. Yes, a lot of memories of fires both large and small, even a forest fire at a nudist camp, but I won’t get into that one now!

I may be in the minority here, but I don’t agree with the oft-repeated “too much fuel in the forest” premise. The notion is that during pre-settlement times, fires ignited by lightning strikes or Native Americans burned unchecked and cleared out the understory trees and brush. Then the U.S. Forest Service as a relative latecomer on the environmental scene was somehow too zealous and “too effective” in fire suppression. Hence the supposed build-up of combustibles and the destructive fires now.

In point of fact, an average of more than four million acres of Western lands burned each year during the 20th century decades leading up to the “too much fuel in the forest” postulation. Believe, me, folks, we were not that effective with fire suppression! Invariably, the largest fires that I was on were controlled only after major changes in the weather. This argument is much too simple and, I believe, driven by political and economic interests eager for greater access to our national forests for logging and other profitable pursuits.

Yes, there is fuel in the forest. There is also water in the swimming pool and if we drain most of it out no one will drown. But I think we would also miss the swimming pool. Climate change (i.e. extended drought cycles and bark beetle killed forests) and cultural factors are the primary causes for the frequency and intensity of forest fires today. Look down the next time you fly west out of Denver and you will see roads and houses spotted everywhere in the mountains. California provides a good example of suburban sprawl gone amok. It is not inconsequential to this discussion of fire—and just about every major environmental issue we face today—that the population of the U.S. has more than doubled since 1950.

The largest and most destructive fires are almost always started by people. The owners of those houses, many of them second or “trophy” homes, have built them in some of the most high-risk areas for fires. And yet they expect firefighters to save them regardless of the peril. Another commonly overlooked reason for Western conflagrations is the oats-like cheat grass (Bromus tectorum). When it dries out and turns yellow each summer, this alien and invasive species creates incendiary burning conditions. In much of the West it blankets the brushy foothills and open ponderosa pine forests. There wasn’t cheat grass during the pre-settlement period.

Turn on the TV news just about anytime during the summer and you will see reporters covering a major wild fire. Invariably, seen in the background are Nomex-clad firefighters spraying water on the flames with a hose. A hose? We might ask what is on the other end of the hose that is seldom shown on the video? Where did the hose and water come from? In the four years that I worked in Idaho I never saw a fire hose or a pumper truck or a fire burning so conveniently next to a road. The TV reporters are there because they can easily drive to the fire. I was on fires when I did not have enough water to drink—we scrounged it unpurified from whatever source we could find. And so I think we can add yet another dimension—intense and sometimes florid media coverage—to the perception of the intensity and frequency of forest fires today versus by-gone years when the U.S. Forest Service was supposedly “too effective” in suppressing them. There were many fires then, they burned millions of acres and certainly impacted the lives of people, but did not receive the media attention they do now for obvious reasons.

Briefly turning this commentary to burning woodlands and prairie in Iowa, the proverbial “moderation in all things” comes to mind. Don’t overdo it. Microbes (bacteria, protozoa, algae, and fungi) and a host of other “critters” from the bottom of the food chain on up are vital to decomposition and the natural recycling of elements—the energy-carbon cycle powered by the sun. The moldering log in your timber—the big oak tree that fell in a windstorm 20 years ago that is now covered with mosses—the leaf litter, the thatch, the random tangles of fallen branches rotting away now—diverse terrestrial life, including vertebrate, depends upon it and also upon some manner of natural “stability.”

One last caveat to burning: It can make your neighbors nervous. Whoever strikes the match is liable for any damages. More than one prescribed “controlled” burn has gone badly.