Root Plates Can be Dangerous, and Interesting

In summer 1984, a very narrow storm, probably a tornado, lurched through our rural neighborhood, including our yard. A tall hackberry tree at the edge of the woodlot toppled and pulled up a root plate of soil about 8 feet high by 12 feet wide by 2 feet thick. Next autumn, that tree was convenient firewood, with the trunk held horizontal. I began cutting the branches and worked my way “down” to the main trunk. When only about three feet of trunk remained attached, the root plate gave a sudden shudder and with the whooshing sound of compressed air, flipped back into the hole it had come from, with a nearly perfect fit. If someone had been in the hole, it would have been a disaster, because the root plate weighed perhaps 2 tons.

This sudden instability was of course a result of me removing the branches and most of the trunk, which were anchoring the root plate. The more “natural” sequence of events is shown in this photo.

This hackberry tree blew over nearly 5 years ago in a summer storm. For several years it still looked somewhat healthy, producing new leaves in spring and even some fruits in summer. But as the dirt steadily fell away from the root plate, there were more and more bare roots sticking out in the air, and the tree was slowly dying of desiccation. Today it is nearly dead.

There is a pile of soil forming at the base of the root plate. Decades from now, the tree will be gone and there will be a little pile of dirt remaining on one side of a shallow hole. If you walk through any hillside woods in late winter after the snow is gone, you are likely to notice these little “pit and pile” landforms where a long ago toppled tree left its obituary on the landscape.

Similar little landforms in the woods are created by children making “forts,” which often consist of digging a shallow depression enclosed by a raised rim of dirt tossed out of the hole, and often covered with a dome of branches that sometimes includes Mom’s plastic tablecloth to shed rain. Years later, these remains are different from the root plate depressions that have the low mound of dirt only on one side.

Sometimes groups of trees topple together because they share the same unfavorable topography and geology. Last summer, a group of five went down in our community woodlot.

Children play in both types of depressions while they last, and the era of use can sometimes be identified by the artifacts left in the dirt. WWII children played with toy soldiers and toy vehicles rather crudely cast in lead, which lasts a long time, and cap guns made of pot metal that shot caps. They also always seemed to have a collection of brass shell casings brought home by relatives who had fought overseas, and from veteran’s parades and Memorial Day services, where salutes were fired with blanks. Coming closer to the present saw a shift from metal to plastic artifacts. Barbie Doll made her debut in 1959 and finding her in a dirt structure gives a clue to the maximum age of the structure.

In this case, they were all growing on a rather steep east-facing hillslope, so they had all been fighting gravity already, which was giving them a lean to the east; and then a storm blew in from the west. When you look at the bottom of the larger root plates here, they contain little pebbles and chunks of reddish dirt. This is the top of an ancient soil profile developed in the clay – rich glacial till, about 2-3 feet below the woodland soil surface. In wet seasons, including last summer, this creates a little perched water table atop the glacial till, and the roots lose their ability to grip the mushy soil. For these trees, in this spot, at that moment, it was the perfect storm.

For many organisms, being older and bigger is often an advantage, with greater mortality among the young and inexperienced. But for a tree, larger also means a bigger sail for windstorms to catch, and risk blowing it apart or blowing it over. Bigger isn’t always better, especially here on the edge of the prairie. West of here, wind, fire, drought, and grazing worked together to limit most tree canopies to the river valleys.

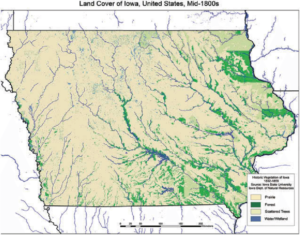

This map is an interpretation of forest vs prairie landscapes witnessed by the original land surveyors of Iowa nearly 200 years ago. I think that it is a somewhat oversimplified interpretation, with many landscapes not covered with a closed canopy of trees being portrayed as prairie. But it nevertheless is clear that the most forested landscapes west of here were in the river valleys.