Sassafras: A Unique Native

In the colorful hedgerow beside the prairie grasses, the orange-red trees are sassafras, the yellows are redbud and the persimmons are still green. Photos by Kate Sulentic.

Back on Dec. 1, 2016, I offered you a story about the historical medicinal aspects of sassafras and its role in the early exploration of the New World by Europeans in “The Strange Tale of Sassafras.” Today, let us take a quick look at this unique native, rarely seen in our area.

With regard to autumn leaf color, there are few other species that can compare in intensity and diversity of pigmentation:

Some sassafras leaves turn a deep garnet-burgundy color. Individual leaves can grade from tangerine to lemon to pale green.

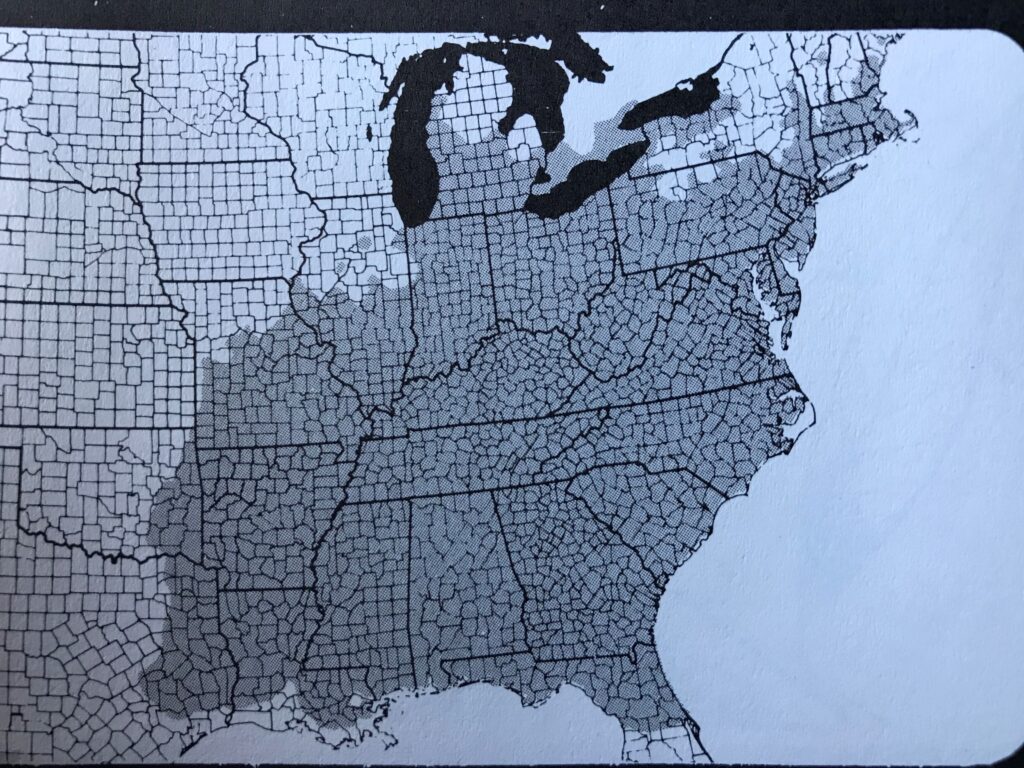

The old literature clearly states that sassafras is native to southeast Iowa. Britton and Brown, whose database is mostly from the late 1800s, list its range extending into Iowa. Rydberg, published in 1932, says its range extends west into Nebraska. Peattie, representing the WWII-era, specifically mentions it being here in southeast Iowa. But the newer, more recent literature is different. Hightshoe’s map, 1988, portrays none in Iowa. Van der Linden and Farrar, 1993, mention a few in the state, which they suspect were planted around homesteads and spread out into naturalized thickets.

This difference between the older and newer literature is seen for other uncommon species also. Both eras represent faithful reporting by people who were there, and there is no mistaking sassafras for any other species with its distinctive leaf shape, fruits, interesting flavor, and growth form. Generations ago, any country child within its range could nibble on a leaf with their eyes closed and tell you what it was. My interpretation is that there were originally scattered outliers of sassafras across Iowa into Nebraska, extending westward from its main range southeast of us. But it is a little tree of the well-drained uplands, too small for lumber or profit. It was simply in the way of plow and pasture, and so it was eliminated as Iowa was converted to industrial agriculture.

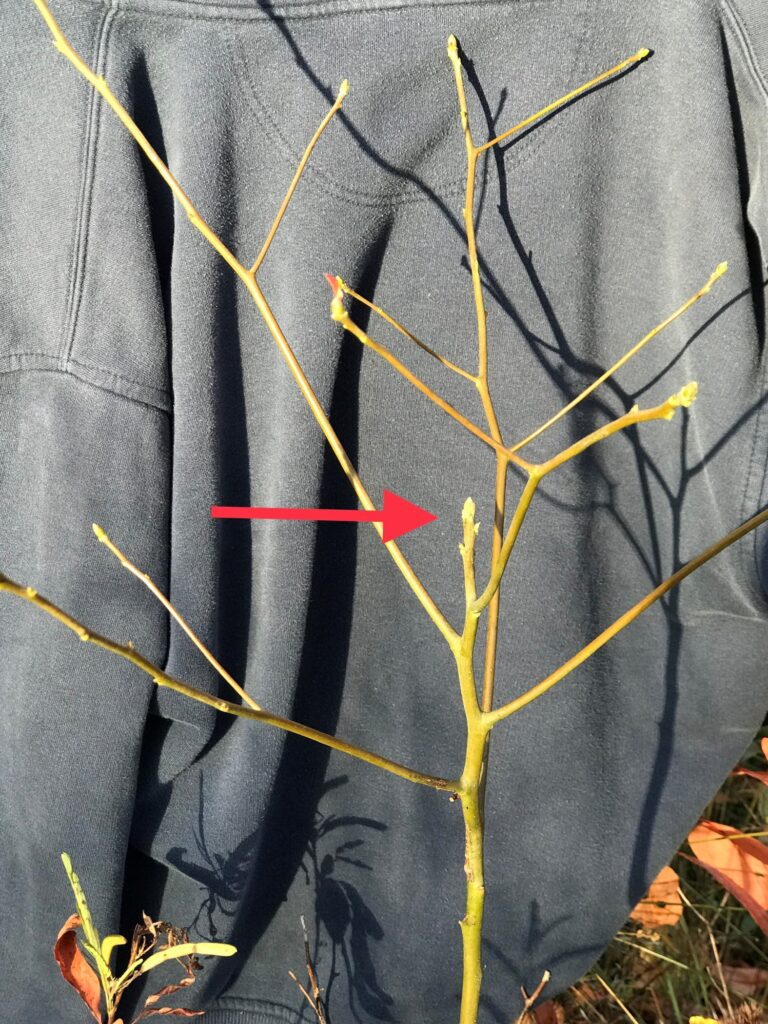

The top of a young sassafras. Note the short central leader (red arrow) and the longer horizontals below it. All this year’s growth.

The young growth form of sassafras is very distinctive, reminiscent of the gymnosperm (conifer-type) trees it evolved from way back in the late dinosaur era. In spring, it sends up a short, central, vertical leader with a lead bud. Then, if things are going well, it adds a vaguely defined whorl of three or four more branches, nearly horizontal, which grow out much more than the central leader grows up. Repeating this each year produces a little tree which grows upward rather slowly, but is wide and open, making it quite successful for a pioneer species needing full sun.

My suggestion is that Bur Oak Land Trust should plant some sassafras thickets on several select properties so that local people can experience the autumn color, unique leaves, unusual fruits, interesting taste, etc. of this species. It is also one of the few host plants for the rare spicebush swallowtail butterfly. The plant needs full sun and good drainage, and will even grow on quite dry sandy soils. Some exist on the arid sand dunes of Lake Michigan as scraggly little shrubs.

Once a little tree gets well established, perhaps in five years, it will send up root suckers close nearby, attempting to form a little thicket. These suckers have no separate roots of their own — they are essentially underground branches — and if you attempt to transplant them, they will die once the umbilical cord is cut. Starting with seed or seedlings is your only practical option.

The fruits are unique, little deep blue ovoids standing up well above the branches on long, slender, brilliant red stems. I tried for several years to get a photo in my yard, and the day they were ripe the birds beat me to them. I finally resorted to completely wrapping a young female tree in a fine mesh net. So I think that this is a little tree worth getting to know, and the effort it takes to grow it.

References cited:

N.A.Britton & A. Brown, 1913, An Illustrated Flora Of The Northern US & Canada, Scribers Sons.

P.A. Rydberg, 1932, Flora Of The Prairies & Plains of Central North America, Hafner Publishing

D.C. Peattie, 1948, A Natural History of Trees of Eastern & Central North America, Houghton Mifflin

G.Hightshoe, 1988, Native Trees Shrubs & Vines for Urban and Rural America, Van Nostrand Reinhold

P.J. van der Linden & D.R. Farrar, 1993, Forest & Shade Trees of Iowa, Iowa State Press