Singing the Butterfly Blues

Across the continental USA, there are about five dozen butterfly species in a group called the “Blues,” which includes a subgroup labeled the “Azures.” All the males are either all blue or partially blue topside, while the females tend toward camo colors with small blue markings topside, but sometimes no blue. Size-wise they are all small and they fly close to the ground to stay out of the wind, so are hardly noticed by us humans. The main food plants for their caterpillars are various legumes, especially lupine, and for some lupine is the only choice. While ants are predators of some caterpillar species, they are caretakers of many Blues in return for sugary secretions.

There are at least six Blues species in Iowa today, not including the Karner Blue, which has been extirpated here and is the focus of today’s blog.

One of the broadest generalists in the large group is the Melissa Blue, which is widespread across the western states and extends into western Minnesota and northwestern Iowa. The Melissa Blue caterpillars especially feed on assorted native legume species and have adapted well to domestic alfalfa. But coming further eastward, into eastern Minnesota and northeast Iowa, the species morphs into a slightly different butterfly, the Karner Blue. The US Fish and Wildlife Service lists it as a subspecies of the Melissa Blue, while Paul Opler, the “dean” of North American butterfly research, considers it a separate species.

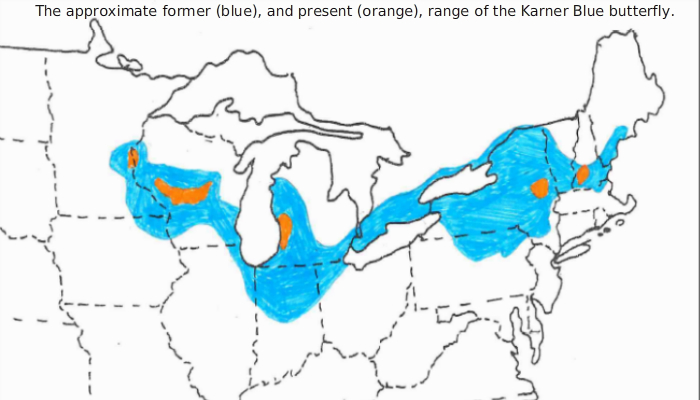

The geographic gap between the Melissa and the Karner is essentially the Des Moines glacial lobe, a landscape of clayey glacial till and wetlands, which does not support lupines. Lupines in the upper Midwest are savanna or open woodland species, and need sandy, well-drained soils. One lupine species (Lupinus perennis) dominates coming eastward of the gap and continues through the Great Lakes region and eastward into Maine. The Karner Blue is completely obligate to this plant, and was confined to an even narrower east-west strip because it couldn’t range as far north into Canada as could its host plant. Unfortunately for the Karner, these sandy soils in a cool climate with adequate rainfall and easy transportation on the Great Lakes were readily converted to potato farms, fruit orchards, pine plantations, dairy pastures, and fire-suppressed woods – all of which excluded lupine. Consequently, the Karner Blue today is extirpated from Iowa, Illinois, Ontario, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maine, and Massachusetts. Remnant populations remain in Wisconsin, Minnesota, New York, New Hampshire, and maybe Michigan. The greatest declines have occurred during the last quarter-century, probably because of increasingly widespread use of insecticides, combined with the more steady loss of habitat. The largest remnant population today is in central Wisconsin – a glacial sand plain that once contained extensive lupine habitat – and which the US Fish and Wildlife says is now less than 0.02% of the original population.

As climate change nudges ecosystems northward, even these little remnants may be lost, because the lupine will not tolerate being pushed off its patches of sandy soil. Fortunately this large-seeded species is easy to grow from seed, as long as you can get seed not already damaged by weevils. Perhaps the best long term way to save the Karner Blue and the wild lupine is to purchase cheap, ruined sandy land on the north side of its range and manage this land as lupine savannas.