The Bugs Around Us

This story originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of Bur Oak Notes, a bi-annual magazine for Bur Oak supporters.

Here’s the thing, Jeff Klahn likes insects. Beetles, especially.

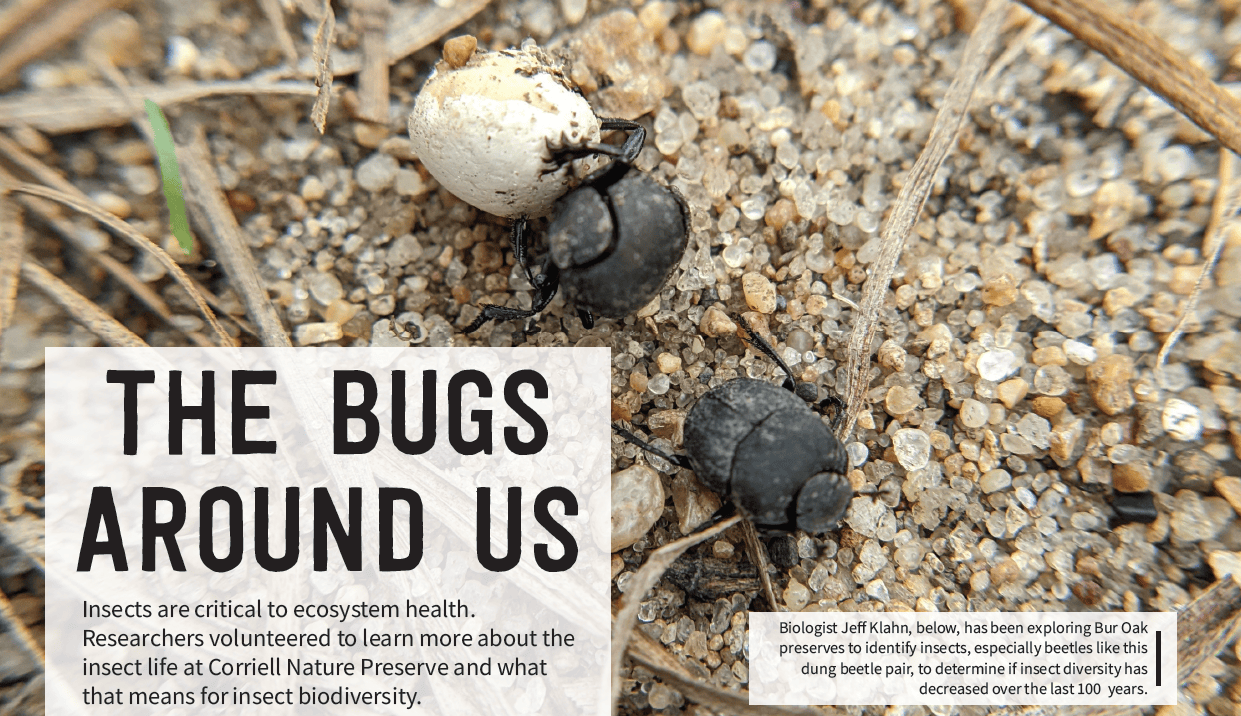

As a lifelong biologist, professor and now lecturer emeritus at the University of Iowa, Klahn has been studying these often-overlooked creatures and surveyed Bur Oak Land Trust preserves to find them.

“We have two questions here,” he said, “there is diversity – the number of species – and abundance – how many individuals there are. I hope to get a handle on the diversity to get a notion of what species are out there.”

Klahn is particularly interested in whether insect diversity has decreased over time. To answer this question, he visited Corriell Nature Preserve, a nearly 200-acre area protected by Bur Oak Land Trust along the Cedar River in Muscatine County, and other protected areas on and off over the last few years to find as many insects as he can. The survey he started at Corriell is one of many he has worked on since retiring about 10 years ago.

“I thought, well, [Bur Oak] might be interested in insect biota on their properties because everybody pays attention to plants and birds and mammals and reptiles, those insects tend to be ignored,” Klahn said, “And that’s a pity because although sometimes these bigger fauna are rare and hard to find, you can always find insects when you go out and look around; they’re doing something.”

Of course, Klahn isn’t the only person to recognize the importance of insects and he won’t waste time retelling why they are so critical to ecosystems when world renowned biologist E.O. Wilson, also known as the father of biodiversity, said it so succinctly: insects are “the little things that run the world.”

Like Wilson, Klahn has spent much of his time examining and appreciating the complete web of life since he was young.

“I’ve always been keen on biology,” he said, “I grew up on the west coast in a little logging town out there and our playground was 10 square miles of area that had been burned up in a forest fire and was growing back in: that’s perfect wildlife habitat. My mother would kick us out the door in the morning and we’d come back for dinner, so I saw plenty of nature.”

He found an interest in beetles in the 1970s while working on biology research projects in Costa Rica. Another group was working on trapping beetles. Carrion and dung beetles are hard to find without bait. They tunnel underground and really only come out for food, plus, they have complex social behaviors.

These beetles will quickly form male-female pairs to claim and guard their food before burying it and feeding their young together. They must pair up quickly and get their food underground before other competitors show up. Aside from ensuring the species survival, beetles consuming these materials has an important ecological function.

“These rich clumps of resources, carrion, dung, things like that, you’ve got to till it back into the soil … which means that you have to break it up mechanically as well as chemically,” Klahn said, “Beetles provide the mechanical breakdown and help to process those materials much faster.”

Without this breakdown, particularly with dung from large herbivores like cattle, the physical pile of waste can hinder plant growth and too much animal waste can leach chemicals from it that make the ecosystem toxic.

The idea of going out and finding beetles that thrive on dead animals or animal waste may sound disgusting to some, but Klahn is quick to say, hey, that’s life.

“Nature is not a very cleanly place … It can be unpleasant but the things you find are striking,” he said.

Although the Corriell survey is more casual with Klahn getting out to survey when he has the time, he has compiled a list of 183 identified species. He said many of the species are particularly interesting because they are only found in places with sandy soil, which is an uncommon feature across Iowa with its majority heavy clay soil and upland and prairie habitats. Sandy soil is an ideal environment for many tunneling insects, including the beetles Klahn loves to study. Another fascinating creature on the list is one many people like to avoid.

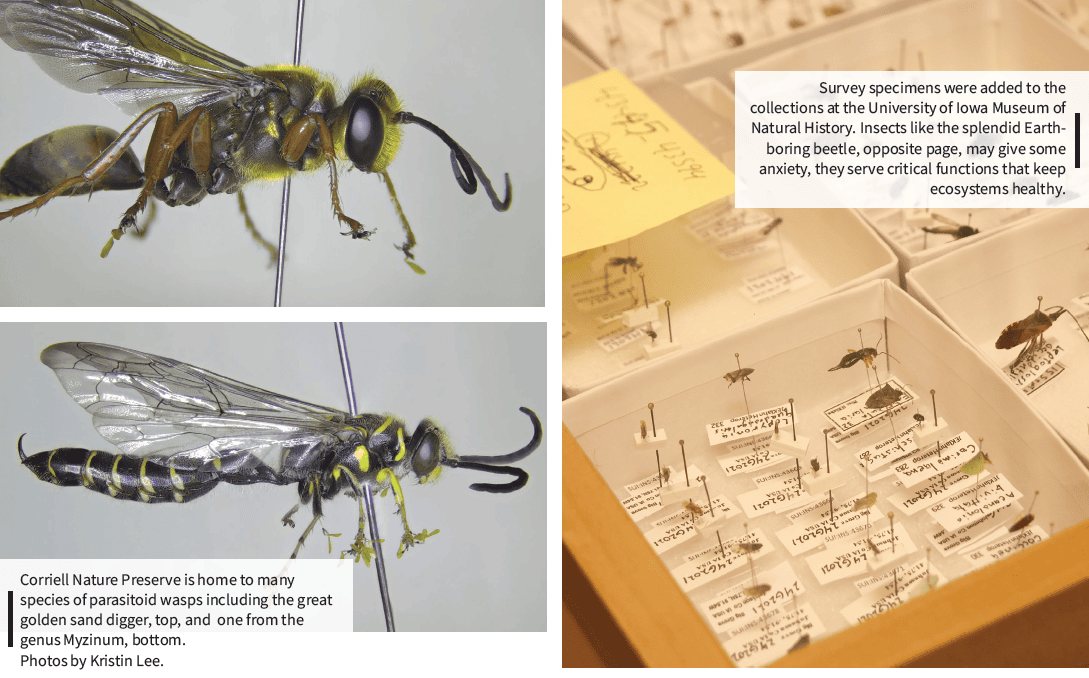

“Parasitoid wasps,” Klahn said, “there is an enormous diversity of these and only a few people pay attention to them, but they are absolute gems when you get them under the microscope.”

These “weird little military drone creatures that are quite beautiful, too,” he said use other insects as hosts for their eggs and eventual offspring. Parasitoid wasps can paralyze the host or deposit their eggs so the host continues to grow within them. Either way, the host will die from the process, leaving the next generation of wasps to continue the cycle.

One local person that does pay attention to parasitoid wasps is Kristen Lee, a local amateur entomologist with a background in biology, who aided Klahn in the survey by collecting and identifying wasp and bee specimens.

“She’s just fantastic,” he said.

Lee was serving as an AmeriCorps Wildlife Survey Specialist at Bur Oak at the time but found her interest in the lives of bees and wasps much earlier through the native plant garden her husband planted in their Iowa City backyard. As she would observe the plants that grew, she would naturally also observe the insects that came to the flowers. Her interest in bees took off during a vacation in London where a postcard with a list of local bee species inspired her to spot each one.

After that, she thought, “I should learn to do this [at home] where it actually matters.”

Since then, Lee has learned from local experts, taken classes, and contributed much of the local location data on the endangered rusty patched bumble bee to community science apps Bumble Bee Watch and iNaturalist, as well as data on many other bees, wasps and general insects.

“If we’re going to conserve the species,” she said, “we need to know where they are.”

The species Lee was most excited to find at Corriell was the southern plains bumble bee, Bombus fraternus. She said she liked the look of the bee with distinctively short hair and sleek appearance compared to other fuzzy bumble bees. It is also a rare species.

The southern plains bumble bee is not listed as threatened or endangered in the US under the Endangered Species Act, but the species is listed as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The IUCN is a network of government and civil organizations within more than 160 countries that work together for conservation and maintain the Red List, a status of animal, fungi and plant species around the world. The data needed to make these determinations and to better manage habitat for species comes from all kinds of databases, including ones built by community science. If you want to do what Lee does, go for it, she said. A person doesn’t necessarily need advanced education or formal training to contribute.

“People get to a certain point and they feel like if they don’t already know it or if it’s not related to something they already know, they can’t do it, but it’s not true,” Lee said, “You just have to try.”

Over the last 6-7 years of surveying, Klahn has collected, and identified to some degree, around 4,000 insect specimens. The insects have been donated to the University of Iowa Museum of Natural History over the years, including all the specimens from Corriell.

“[Receiving the specimens is] really exciting for us because, for the most part, our collections here at the museum of natural history are historic, which means that most of these insects we got from collectors who were active in the 1890s up through 1910,” said Cindy Opitz, director of research collections at the museum, “Now Jeff is out there collecting new material and that material can be compared with the old material and inform biogeography studies about habitat loss, which insects used to be in which places in Iowa.”

“His specimens will also speak to the health of restored prairie,” she continued, “If we see prairie insects coming back to those areas where prairie was destroyed and is now restored, that’s also exciting.”

According to the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, “protecting land slows biodiversity loss among vertebrates …” and a study published in 2016 in the journal Nature found “even within some human-dominated land uses, species richness and abundance are higher in protected sites.”

The Cedar River corridor has several nonprofits and agencies protecting land within it, including Bur Oak Land Trust. With larger areas of contiguous land protected, wildlife has greater access to the food and shelter they need to survive.

“That’s the value of all these properties, each one, they’re not just alone, they are links in a chain,” Klahn said, “and I think that’s responsible for supporting the kind of diversity we still have out there.”

So, what can the average person do to support the insect communities where they live? There are two things that are pretty simple but make a big impact. The first is to turn off the lights.

“Night flying insects are severely disoriented by lights and everything you see flying around your house lights at night in a swarm,” Klahn said, “they are wasting their energy and they’re not doing what they have to do to survive and reproduce.”

The second thing is to generate habitat. A small prairie patch can provide more places for insects to live, eat, reproduce, and generally move around. A patch with many different plant species will also attract and sustain many different insects. Another option is to support local conservation efforts.

“Bigger patches of habitat are much more useful than little ones and that’s why I support land trusts,” Klahn said, “because trusts like Bur Oak and The Nature Conservancy and all the others can get land in fairly big patches, and you need that because animals have to be able to move around between habitats and opportunities. This is how they survive. If they’re stuck in one place, sooner or later they have no place to go, and bad things happen.”

Surveys like the one Klahn is doing are the best way to know how insect species are faring in Iowa, and if you’re still hesitant about insects, one way to start supporting them is to be curious when you see that wasp flying around your picnic or that spider in your basement rather than trying to get rid of them. Klahn understands the hesitation to fully embrace the bugs around us, but it’s important that we do.

“[Insects] generally have hard shells, too many legs and things sticking out all over,” he said, “but what can I say, we should learn to appreciate them for what they are. And they are critical enough, it’s quite true that if you essentially wipe out insect life, you’ll wipe out most environments.”

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Night Flight: Learn more about the importance of darkness for many flying creatures at this free family-friendly event!