Walter Rothschild’s Museum Legacy

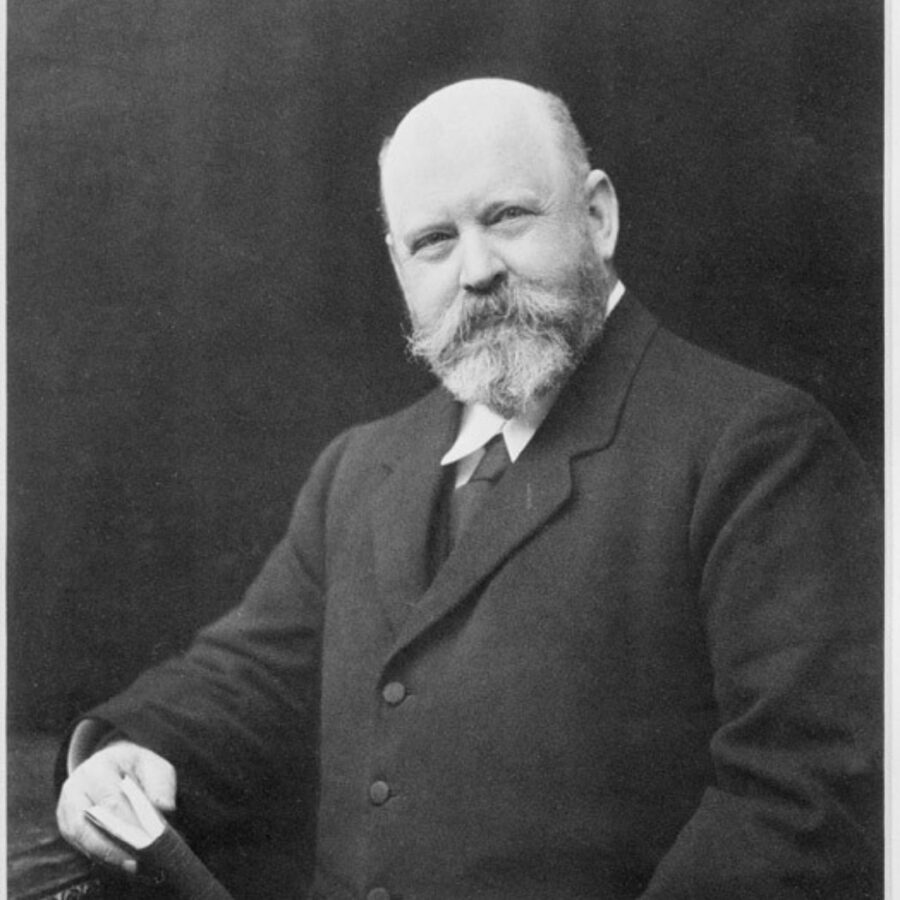

No sketch about museums and species would be complete without including Walter Rothschild. Born into the extremely wealthy banking family of Britain in 1868, he lived all his life at Tring Park, the family estate near London. We know a lot about him because his niece Miriam Rothschild knew him well and wrote his biography titled, “Dear Lord Rothschild.”

The family’s expectation was that he would grow into and eventually take over their banking empire. But he scandalized the family by having no interest in money management and making awful business decisions. It also didn’t help that in class-conscious Britain he was regularly seen with one of his many mistresses. And it was hard to not notice him, standing 6-foot three inches tall and weighing more than 300 pounds.

While his personal life was chaotic he was deeply interested in biology, especially in species questions. While most people with these persuasions go off to see the world, Walter, with his immense wealth, had the world brought to him. As a very young man he had a small herd of zebras, a flock of kiwis and a collection of giant Galapagos tortoises in residence at Tring Park. By 1888, he had approximately 400 collectors in his employ around the world, plus accountants and bookkeepers to track them and keep them paid and supplied. By the end of that year he owned approximately 50,000 bird skins, butterflies and moths, prepared and organized. The following year he opened a museum at Tring Park, which catered to an estimated 30,000 people in its first year. It was one of the most admired museums of its era, designed by scientists who understood the implications of Darwinian evolution, and built by skilled craftsmen.

While his business acumen approached zero, due to total lack of interest, his memory for details about natural history was amazing. Years after receiving some rare butterflies from a remote island, he would remember their details when opening a new crate of specimens from a distant island. And upon consulting his collection and finding that they might be the same or related species, he would send out his collectors to intervening islands to fill in the gaps. More than anyone else, Walter brought geography to natural history.

By the end of his career, his niece Miriam estimated that he owned about 300,000 bird skins, 200,000 bird eggs, more than 2 million pinned Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) and the largest collection of scientific books and publications in the world. He, along with associates using his collection, described and published an estimated 5,000 new species.

Walter’s conservation record is mixed. In his day, naturalists expressed fears that his vast collections were depleting the natural world and that rare species might be driven to extinction. If you want to study, for example, rare Hawaiian sicklebills today, there are probably more in the Rothschild collection than living on the Islands. But when he became concerned about the fate of some favorite species, he was known to simply rent an entire island and have it managed according to his instructions.

Late in life, Walter’s extravagant lifestyle became even more messy, and he was probably being blackmailed by a mistress, although details were never revealed. In 1931, he sold most of his entire bird collection to the American Museum of Natural History in New York for a quarter-million dollars. Others estimated it had cost him about one million dollars to acquire.

Today, when tricky species decisions are heavily influenced by DNA analysis, Walter’s collections are invaluable. So while generations of Rothschild bankers have quietly come and gone, the efforts of the black sheep of the family are still well known to naturalists, conservationists and scientists around the world today.