Wetlands for Water Cleanup

For centuries, in the Western world, swamps have had a negative reputation, and this still carries over in our language today – the Great Dismal Swamp of Virginia, the political morass of Washington, DC, a boat getting swamped, …. These places were unproductive wastelands, a place to dump trash, a place to dispose of unclaimed bodies (some of which have been perfectly preserved for centuries when buried in acid peat).

When indoor plumbing arrived in cities, swamps became a handy place to dispose of sewage. There grew a bit of recognition that some sort of treatment was happening, and over the past century some European cities built “reed beds” for sewage treatment, which we would call constructed cattail wetlands.

You might remember the vast quantities of Agent Orange we sprayed on Vietnam. It was noticed that in some swampy areas the herbicide vanished quite quickly. Bill Wolverton was assigned to find out why, which he did with test plots in southern swamps on military bases. He learned that oxidation and reduction chemical reactions occur side by side in swamps, driven by microflora and fauna, which are quite efficient at breaking down complex carbon-based molecules, including Agent Orange. After the war, he moved onto the space agency, which was (and still is) thinking about colonizing Mars, and he demonstrated that constructed wetlands were efficient at breaking down human waste. He made this practical by developing household septic systems with wetlands, suitable for our southern states, and published a flurry of papers on the topic in the 1970s and 80s, which caught the attention of other researchers.

Arcata in Northern California had a derelict waterfront opening into Humboldt Bay, left to decay from when it was a logging and lumber town. This included an oceanside landfill condemned by the Board of Health, and raw sewage discharged into the bay. But in the early 1980s, reimagined and designed by Bob Gearheart, George Allen, and Frank Klopp, the whole mess had become converted into a tertiary treatment wetland. By 1990 it had 5 miles of trails, serious birding, and its own salmon run, and was becoming a tourist destination, selling t-shirts inscribed with “Flush with Pride.”

There were others. In 1985, the Iron Bridge wetland, treating the sewage from Orlando, Florida, was created from 100 acres of formerly farmed wetlands. It quickly became great habitat and part of their park system. A graduate student and I were going to camp overnight there on one of the berms, until we noticed how large some of the alligators were.

Secondary discharge from Orlando into Iron Bridge wetland

Overview of Iron Bridge constructed wetland

In 1994 Stanley Consultants evaluated the possibility of using constructed wetlands for final (tertiary) treatment of Iowa City sewage to 2020. Depending upon assumptions used, they concluded that it would require a wetland from 1039 to 1665 acres in size (there are 640 acres in a square mile), and the city abandoned the concept.

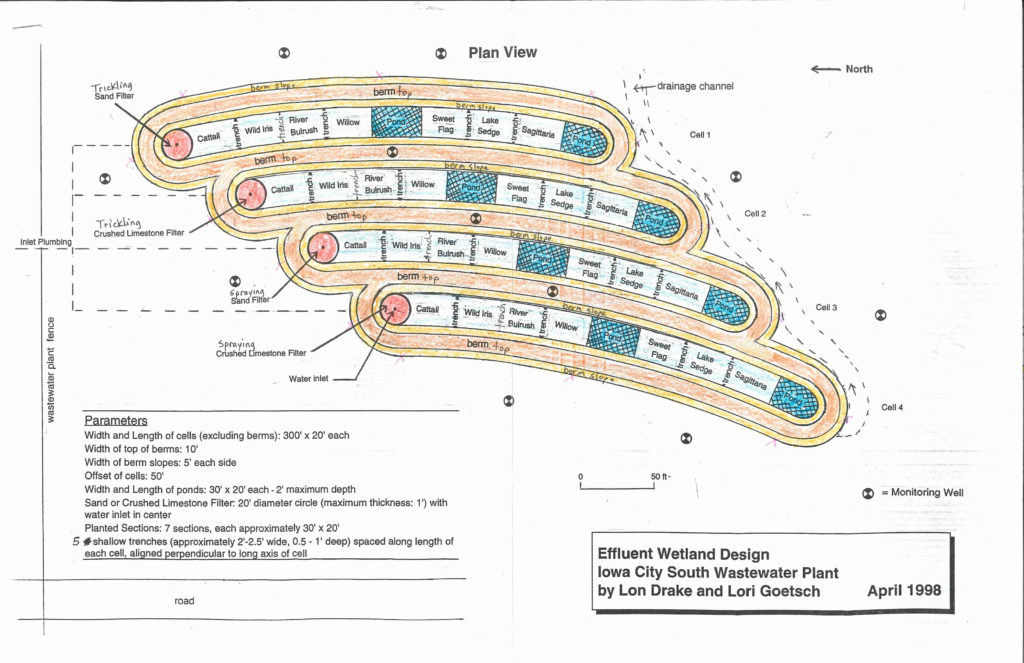

However, graduate student Lori Goetsch and I reevaluated the assumption that went into their estimates and decided we could do better. Dave Elias agreed to build a four-acre test plot, which Lori planted and monitored.

One of the largest hurdles to final cleanup is adequate removal of ammonia in winter, so the test plot especially focused on different ways to better accomplish this. Our conclusion was that the wetland area still needed to be at least one square mile to meet discharge requirements to the river. And following the example of Arcata and Iron Bridge, the city could wind up with a square mile of wetland habitat and park. We thought this a viable possibility because farmed wetlands already warp around the Wastewater Facility on two sides and would need only small modifications to restore to functional wetlands.

The city however upgraded their final discharge via traditional engineering methods, with a very compact design that fit on their existing property. And it does work very well. The final discharge meets drinking water standards about 99% of the time. Dave and I have both drank glasses of it, and when chilled it is hard to tell from some bottled waters.

It still seems sorta wasteful to just be dumping 5 million gallons of drinking water per day into a filthy river. A greener option, with more conservation value, would be to run it through a large constructed wetland, creating habitat and a park. And the plants would remove the soluble nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, which contribute to sliming up the river downstream. So how do we get this funded?

Tags: Lon Drake, water treatment, wetland