Wolverine Stories: Citizen Science Furthers Environmental Conservation

In the summer of 1996 I was at a barbecue in Teton Valley and in attendance were two special friends. Dick Staiger, an amateur naturalist, was a 4H club leader of a group of teenagers who had specialized in natural resource projects. Jeff Copeland, a former game warden, was doing research on wolverines as a graduate student at the University of Idaho, eventually becoming the nation’s leading authority on Gulo Gulo, and founder of The Wolverine Foundation. Peering eastward at the magnificent Grand Teton mountain in sunset alpenglow, Dick posed the question to Jeff, “Are there wolverines in the Teton range?” Jeff, whose research had been mostly in the Sawtooth and Glacier Park mountains, replied that there had been occasional anecdotal sightings, but nobody had actually studied and documented their presence. “What if,” says Dick to Jeff, “our 4H club were to build some traps and to actually catch a wolverine. Could you possibly be our advisor and sponsor, as part of your research, to assist us in getting permits, and provide some professional oversight? Then Gary could do the radio tracking.” Thus was launched an extraordinary research project, which remains the longest running study of wolverines in the contiguous United States.

Bait at trap site

That winter, with Jeff’s direction, three very heavy duty log box traps were constructed by the 4H kids and in January were placed at sites accessible by snowmobile from the Grand Targhee ski resort. Sites were baited by road kill mule deer hanging from a tree, and traps were monitored from one of the kid’s home by a trip switch on a radio collar attached to the trap. Jeff advised that a lot of inconvenient non-targeted captures would occur for every actual wolverine. Yep, foxes, bobcats, long-tailed weasels, and American martens would regularly set off the alarm radio signal. Jeff said “when, as you approach the trap, you hear the most blood curdling growl imaginable, you have caught a wolverine.”

On April 4 an adult female was captured and nicknamed Wolverann by the kids. Thus began a project for me, making locations once a week for the next 10 years, to the benefit of the declining wolverine population. During the next winter they trapped three more animals and suddenly, Wyoming Game and Fish, the National Park Service, and the US Forest Service became very interested and funded the project. This meant that now I could actually be paid for my flying.

Wolverines are the largest member of the mustelid family, adults ranging from 25 to 50 lbs., and are noted for their strength, aversion to human contact, and alleged mean temper. I once saw a wolverine chase a black bear off a moose carcass. A wolverine’s neck is thicker than it’s head, so conventional radio collars do not work. When one was caught, the team, along with folks from the Forest Service, Wyoming Game and Fish, and Grand Teton National Park accompanied the volunteer local vet to the trap site to set up a portable operating table and implant a radio transmitter in the abdominal cavity.

The 4H kids became celebrities of sorts, conducting well received weekly tutorials for the guests at the Ski resort, with maps showing the large movements of the animals. The kids were impressed by how little the general public knew about wolverines, and were quite amused by one lady who thought a wolverine was a female wolf. Some of the kids, with parental consent, were rewarded by going along on a tracking flight.

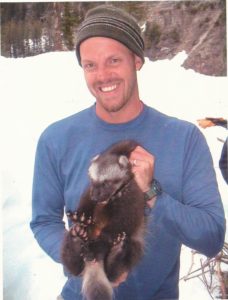

Wolverine kit from a den with snowshoe feet

In 2000 the project was taken over by Hornocker Wildlife Institute and The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). At this time, after trapping the same six animals over and over, it was determined that six was the entire population of the Teton Range and it was time to expand the study. The WCS conducts worldwide research on endangered species, with emphasis on predators. In addition to a PhD staff coordinator, they had a crew of seasonal hard core backcountry mountain skiers who followed the locations on the ground to document food sources, habitat, and den sites. Keep in mind that these hearty animals live, particularly in the winter, in extremely rugged country at or above timber line. In the spring the trackers would visit the dens to capture and radio equip the young kits. Wolverines, particularly males, defend huge territories. The young can travel great distances in search of a new territory, and were found in the Wyoming range to the south, Wind River range to the east, and Centennial range of Montana to the north. A male captured as a kit in the Tetons traveled the entire length of the Wind River Range and was located in Colorado, where wolverines had been absent for 90 years. One of these dispersant animals was caught by a trapper in the Centennial range, which no doubt contributed to elimination of the wolverine trapping season in Montana, the last holdout state outside of Alaska.

This project was a very rewarding experience for me and a tribute to what can be accomplished in conservation by public-private partnerships and was all initiated by a volunteer, youthful group of citizen scientists.